Lampblack is a form of carbon. You can think of it as something like very, very finely divided charcoal. Because it is so incredibly fine, a small amount covers a large area giving an intense black color. It forms the basis of the best traditional black inks and has been used to many other ends from shoe polish to blackening gun sights. Lamblack’s extreme opacity and complete resistance to fading are excellent characteristics for use in the arts

Lampblack is a form of carbon. You can think of it as something like very, very finely divided charcoal. Because it is so incredibly fine, a small amount covers a large area giving an intense black color. It forms the basis of the best traditional black inks and has been used to many other ends from shoe polish to blackening gun sights. Lamblack’s extreme opacity and complete resistance to fading are excellent characteristics for use in the arts

Lampblack can be made from burning oily or resinous materials, while collecting the resulting soot. The pitch of pine trees and other conifers make good lamp blacks, as do oils burned with a wick. It has also traditionally been collected from the inside of oil lamp mantles (the clear glass covering over oil lamps), thus the name. The trick to producing it yourself is to burn the material in such a way that combustion is incomplete. When combustion is complete, the carbon is fully burned, but if the flame is interrupted, or just plain inefficient, some of the carbon remains as soot along with other unburned chemicals. The rising black soot can be collected on a metal plate, bowl or flat stone.

Using a large and lumpy, or long, wick will usually create a lot of soot. Another way to create incomplete combustion is to interrupt the flame. You may have noticed that when an object is held in a candle flame, soot results. When the wick is trimmed or made properly and the flame is burning cleanly, the carbon will be completely burned to up at the tip of the flame and no soot results. The truth is that it is somewhat challenging to make wicks which do NOT soot! The modern candle wick is an exception, not the rule. But for making lampblack, you want a whole LOT of soot, so make that flame as dirty as possible.

A good way to make lamp black under field conditions is to make a small table like arrangement of stones. Pitch or pitch saturated wood from pine or other conifers is burned under the top plate and the soot brushed off with a feather occasionally. I have some picture of that somewhere, but they are like that old kind that are on paper... Any kind of oil lamp arrangement with a plate of some kind on top will also work fine. A tuna can with the lid left partly attached and bent down to form a ramp into the oil is an easy solution.

Lampblack is not at all easily mixed with water. In fact, it is remarkably difficult to get the two together. One time I was tattooing my friend Wylie’s leg (I have pictures of that somewhere too...) with pine soot and figured out that if I spilled beer into the ink, it mixed easier. Yay for beer! It can be mixed with plain water sometimes if a very small amount of water is used, but it can also be almost impossible and a drop of alcohol helps break the surface tension. Lamp black is much used for tattooing around the world, being much finer than charcoal. I have two small tattoo test spots on my leg made by slicing the skin with obsidian and rubbing stuff in. The one with charcoal is uneven, while the one with lampblack is much cleaner. A third made with iron oxide (red ochre, a mineral pigment) is long gone, having faded away completely.

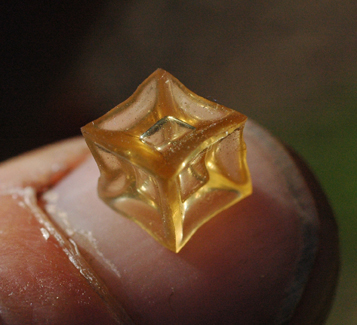

Often lampblack is somewhat oily containing compounds created by the heat destruction of the oil or pitch that are not pure carbon. The lampblack can be purified to an extent by re-burning it in an oxygen free environment. If put in a small sealed tin, it can be burned in a fire to clean it up a little. My results calcining soot this way have been mixed, and I’m unsure whether it is necessary. Another old book (quoted below) recommends packing into an open ended tube for re-burning. I'll try that next time.

Asian inks are usually made as a solid stick by mixing lampblack with a small amount of collagen glue made from hides, sinew or especially antler. The stick is then rubbed up with a little water on a special stone and the ink used immediately. I hope to do almost all illustrations for paleotechnic’s publications with this type of home made ink, and other home made art materials, from here on out. Carbon ink works great with a feather quill pen (that'll have to be another post) What is called india Ink is originally a soot based ink as well, but in liquid form. Since I lost the last ink stick that I made (someone probably threw it out, because it looked like a fossilized anteater turd, though it was perfectly functional), and have to make another, yet another future post may just have to cover ink making in detail! For now, you know what lamblack is, and how to make it and you can build from there. If you just want to blacken your gun sights, or whip up some corpse paint, it's easy to make a small amount of lamp black with a candle or chunk of pitch. Another brick in the wall of self reliance.

I’ll leave you with a couple of quotes from old books scrounged up by using a google books search limited to the 19th century.

Technical Repository, Volume 11 T Cadell, 1827

Black shell-lac varnish.—Shell-lac varnish may be rendered black, by mixing with it with either ivory, or lamp-black. The editor has frequently used, and always preferred the latter. It should not be used as sold in the shops, being then greasy, as the workmen call it, and will neither mix or dry, well. Sometimes the lamp-black contains particles of plaster, from the walls of the chambers in which it is made; this, of course, should be rejected.

To prepare lamp black for use.—Press a portion of it into an earthen or metallic vessel, which may be made red hot in the fire; for small quantities, a tobacco pipe, a piece of a gun-barrel, or any other metallic tube, will answer the purpose perfectly well. It is not necessary to close the vessel, but the powder should be well rammed in; place the whole in an open fire until it is red-hot throughout; this may be known by the lamp-black ceasing to flame at the exposed parts; take it from the fire, and allow it to become quite cool before you remove it from the vessel, otherwise it will burn into ashes. Lamp-black, thus prepared, will mix readily with water, will dry well in paint or varnish, and will be improved in colour.

To mix the colour with the varnish.—Rub the lampblack up with a little alcohol, spirits of turpentine, or weak varnish, taking care to make it perfectly smooth before putting it into the cup with the varnish. To give a good black colour, the quantity of lamp-black must be considerable; this, it is true, will lessen the brilliancy of the varnish in some degree, but a thin coat of seed-lac, will diminish this fault. When only a small quantity of blackvarnish is wanted, it may be made by dissolving black sealing wax in alcohol. Sealing wax being composed principally of shell-lac. But little heat should be employed, or the black colour will be precipitated.

Five Thousand Receipts in All the Useful and Domestic Arts: Constituting a Complete and Universal Practical Library, and Operative Cyclopaedia

A. Small, 1825

Lamp black may be rendered mellower by making it with black which has been kept an hour in a state of redness in a close Crucible. It then loses the matter which accompanies this kind of soot.;

TO MAKE PAINTS FROM LAMP BLACK.

The consumption of lamp black is very extensive in common painting. It serves to modify the brightness of the tones of the other colours, or to facilitate the composition of secondary colours. The oil paint applied to iron grates and railing, and the paint applied to paper snuff boxes, to those made of tin plate, and to other articles with dark grounds, consume a very large quantity of this black. Great solidity may be given to works of this kind, by covering them with several coatings of the fat turpentine, or golden varnish, which has been mixed with lamp black, washed in water, to separate the foreign bodies introduced into it by the negligence of the workmen who prepare it After the varnish is applied, the articles are dried in a stove, by exposing them to a heat somewhat greater than that employed for articles of paper...”

TO MAKE A SUPERIOR LAMP BLACK.

Suspend over a lamp a funnel of tin plate, having above it a pipe, to convey from the apartment the smoke which escapes from the lamp. Large mushrooms, of a very black carbonaceous matter, and exceedingly light, will be formed at the summit of the cone. This carbonaceous part is carried to such a state of division as cannot be given to any other matter, by grinding it on a piece of porphyry. This black goes a great way in every kind of painting. It may be rendered drier by calcination in close vessels.

The funnel Ought to be united to the pipe, which conveys off the smoke; by means of wire, because solder would be Melted by the flame of the lamp.