Why I stopped selling at the local Farmer's Market, due to red tape, health and new rule changes.

Some I'itoi Onion Bulbs Available for Subscribers

I’itoi (pronounced E-E-toy) are small and prolific multiplying onions. The story goes that they were acquired from the O’odham people in what is now Arizona and N. Mexico. They produce a very small Shallot like bulb that can be peeled and eaten, or they can be used as greens or pulled off during the growing season for “scallions”. They are very rare at this point and were put on the Slow Food movements Ark of Taste a list of endangered food varieties. I tossed a bag of old dried up ones that I thought were probably dead out in the rain a month ago, and a lot of them sprouted, so I thought I’d pass on what is left to readers of this blog rather than tossing them in the compost. These are the ones that were too shrunken to sell, though perfectly viable, and now they are just barely hanging on for dear life. They have a small core of viable bulb left and I think that if they are potted up soon most will still grow out. You really only need one as they are very good multipliers. I made up small packets of about 8 bulbs and tossed in a small sample seed pocket/packet of bulgarian giant leek seeds in each. There are about a dozen packets ready to ship, first come first serve if you pay shipping, which just $1.50 should cover. You can paypal that to me after contacting me through the contact link on this website. This is offered for people who are subscribed to my blog.

I don’t know much about cold hardiness of I’itoi. They certainly do fine with light freezes, but growing them outside in really cold climates is going to be a bit of an experiment. I'd appreciate any reports back on how they do. These bulbs are barely hanging in there, but they are tough little guys and still have a living core waiting to find some soil and water. Plant them immediately. In warm climates, plant in the ground now. In cold climates, I’d start them in a pot indoors and then plant out when warm weather arrives. They reproduce like crazy and even if only one survives, you’ll have plenty to share, replant and eat soon enough. I started with just a few and have sold and given away many hundreds of bulbs.

If left in the ground, they’ll form a dense cluster that can contain hundreds of small bulbs. If replanted singly and well tended, they will form much larger bulbs than if left alone, but again they are still quite small.

First come first serve. Contact me through the contact link on this page. Again, this is for people who are subscribed to my blog and they'll probably go fast, so don't contact me next week or next month or next year. I'll probably have them on ebay again this summer and I would think that they will be more widely available from seed suppliers soon.

A google search will turn up a little info on I'itoi onions, but there is only so much out there. This link is a good page to check out for more info.

And This video

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uo6n9704vcE

Saffron Dreams: Musings and experiments in growing Saffron

I like to cook intuitively with what happens to be on hand, which means having a certain familiarity with my ingredients. Recipes are just guidelines in my world and not to be taken at face value, ever. I’ve never had enough Saffron around to become familiar with it to the point that I can use it with any confidence. When my mom brought me a small box of quality saffron from Spain, I had a chance to become a little more familiar. With Saffron now on my radar, I of course decided I should grow the stuff instead of buying it. I mean if we can grow the stuff here, why import it at 80.00 an ounce? Saffron seems to be capable of growing in a fairly wide variety of climates from England to Afghanistan. Then I could sell the bulbs and promote the idea of growing it and start a local industry and.....

A laptop surfing safari turned up a few small scale growers focused on high quality Saffron for local consumption, but none of them in California. Aside from these geeky boutique producers who have been bitten by the Saffron bug, saffron production seems to be left to areas where it has long been cultivated.

Saffron’s peculiarly unique flavor is subtle and pervasive at the same time. A few threads too many and it goes from enhancing your dish to ruining it. Fortunately, it’s intensity means that only a few threads are required and if it wasn’t so intense, no one would likely be able to afford to use it at all, nor probably bother to. The part used is the intensely red stigma of a pretty little purple/blue flower named Crocus sativus, the stigma being the female part that receives the pollen. The Latin name is probably pronounced like kroak-us sa-tee’-vus, or sat’-i-vus but no one really knows for sure because Latin is a dead language. So just say it however you want to and if anyone flicks you shit for pronouncing it wrong, just follow Jepson’s advice of The Jepson Manual: Higher Plants of California:

"... practice what sounds good to your ear; conviction is important." "When someone presumes to correct your pronunciation, a knowing smile is an appropriate response."

That's always worked for me :D

Soil Banking With Biochar: proposition for a migrating latrine system aimed at permanent soil improvement

"The idea is to have a sort of trench system that would serve both as a latrine, and as a means of permanently improving the soil."

This proposal is built around the concept of using charcoal to permanently improve soils. If you’re not familiar with that idea, a little reading on biochar might be helpful.

(EDIT: Ok, I just posted this yesterday, but the original title sucked, so I had to take action. The more I've thought about this idea today, the more I'm inclined to think that viewing it as just a latrine is way too limiting. A system of soil improvement like this could serve to accommodate all sorts of rubbish and organic refuse. I always thought that if I built a nice outhouse someday, that I'd make a sign for it that said Bank of Fertility (make a deposit:). I like that concept. I'm going to go with the term Soil Banking for the concept of a migrating soil improvement system using an open trench. While making daily deposits of doodie makes eminent sense for such a system, there are so many more things that could be tossed in the mix. All people who live in the country that don't have access to landfills, have rubbish heaps or pits of some kind. What I'm proposing is that we use that open pit, and the material added, to a high level of advantage toward the end of permanent soil improvement. At this point, I can only see a big open pit, placed in the right area, to be an outstanding opportunity. The idea of permanent soil improvement, made possible by the addition of charcoal, is really compelling. Dead animals and parts, rotten wood, old natural fiber clothing, shells, bones, ashes, seedy weeds that are best not put in to the compost, anything else that plants or soil life can feed on that the chickens can't eat, or that we don't want to put in the compost for whatever reason, and of course poo and charcoal, all added as they occur. And of course adding whatever other amendments, like lime, rock powder or trace minerals might make sense too, depending on circumstances. Over many years, this system could add up to an ever expanding bank of super soils that will probably continue to be superior for decades, if not for centuries. So there it is, Soil Banking. "What should I do with this dead maggoty possum?" "put it in the soil bank with a few scoops of charcoal and some dirt" "yeah, okay, I was going there to make a deposit anyway!" "righteous dude, high five!" Now back to regularly scheduled programing.)

I’ve been knocking this idea around in my head for a while. Actually, maybe it’s been knocking me around it just want's me to think that I'm knocking it around. It started when I was thinking about ways to use the pit after pit burning charcoal in a long trench. The obvious use was to bury the biochar in it instead of digging another hole for that. After all, it’s one thing to make all that char, but then you have to dig it into the soil, which is a butt load of work. In this climate, outside of irrigated garden beds, I think getting the char pretty deep is probably a good idea. After june, soil moisture is scant near the surface. If the char was buried lets say only 12 to 18 inches deep, that puts it in the zone where roots are mostly on idle for the summer. No moisture= no root activity to speak of. Charcoal is a great retainer of moisture, but it’s not that great. I’m talking about unirrigated areas for orchards and perrenials, or maybe for dry farming crops. If the char was more like 3 feet or 1 meter deep, it would be of much more benefit to plants in the summer season.

Once I thought about it for a bit, I realized it doesn’t make a ton of sense to keep digging new pits just to burn the charcoal in. it’s not like I’m probably doing the soil any favors by cooking it anyway. A central permanent burn area, with a more permanent pit arrangement would probably make more sense, or just burning by any number of methods wherever the wood happens to be. Charcoal is light, so moving it is not an issue. Moving brush and wood is a whole lot more work. In most situations, it’s probably not relevant how the wood is charred, the idea of using the burning pit as a latrine was just a path into this idea.

So let me just hit you with the basic idea and then we can bat the details around a little. The idea is to have a sort of trench system that would serve both as a latrine, and as a means of permanently improving the soil. Once the pit is dug, there are limitless possibilities for amendment with all sorts of substances, and for changing the soil’s physical composition. That’s pretty neat! Also, normally, it would be a fair amount of labor to mix in all of that stuff all at once. As a latrine though, you’d be mixing it in gradually day by day while doing something you have to do everyday anyway. Lets say you wanted to end up with about 20% charcoal in the soil. One poop, one scoop of charcoal, four scoops of dirt and small amounts of whatever other substances you might want to toss in there like lime, wood ashes, sand, phosphate fertilizers, trace mineral fertilizers, organic matter, etc. I’m already digging holes for the current pit latrine used here on the land, but this system would utilize part of that labor to a more useful end.

This system makes sense to me for soil improvement with biochar under my type of conditions. It seems likely that the terra preta soils of the amazon might have been made with some similar approach... like pits into which compostables, broken pots and excrement might be disposed of and covered gradually with dirt and charcoal. I'm not experienced enough with using biochar here to be totally convinced this method will be worth the effort, but I think there is a very high probability that the results will be awesome, easily high enough to jump right in and make the investment to try it.

I’ve never really gotten the latrine scene together here. We’ve always used a pit toilet- dig a pit, drop in a little dirt or organic matter here and there till it’s full, and move on. I’ve tried to put them where I want to plant a tree, but it doesn't always work out. The one site I have actually planted directly on, the tree died, twice even! That might just be due to drought, but suffice to say, it hasn’t worked out very well for me as a system. Also, I’m not convinced that even a pit full of manure is really a very permanent soil improvement, and it will have a limited window of fertility. I’ve thought to eventually build something like the Ecosan drying pit toilet system, but that could be some time away in the future. Thinking back now, 8 years of being here most of the time day in and day out, I could have improved a lot of soil using my new proposed system. The pits would fill up quickly, because so much dirt would be added back daily. It’s a lot of digging, but it’s easier to dig a wide trench than to dig a single deep and narrow pit. Also, it is assumed that soil improvement is an important goal, so the digging is not superfluous work. It is also spread out over much time. Consider digging char into a 40 foot long x 5 foot wide x 3 foot area all at once versus over the course of a year or so. The trench could be dug in sections as needed, or when convenient.

In the days before plumbed toilets, public latrines were a major issue in population centers. I’ve smelled enough latrines to know how horrid the stench must have been. It was proposed to use charcoal as a deodorant and the resulting sludge sold as fertilizer. I think this method was probably successful where implemented, but it wasn’t too long before they started washing it all away into rivers and off to the ocean, which of course we mostly still do today, just in a somewhat more refined, but also much more resource intensive way. Point being, charcoal is the ultimate deodorizer. Imagine an outdoor latrine with no odor.

Having been called on that day to attend a meeting of the Board of Health, held at the workhouse, I was at once struck with the intolerable and sickening effluvinm which, arising from the sewers, cesspools, and privies, pervaded every part of the establishment; and which, with the chlorine, which was being evolved in every direction for the purpose of correcting it, formed a compound of villanous smells, which no stomach but one accustomed to it could for a moment tolerate. Your very active and efficient inspector, Captain Hanley, told me that he had done everything that could be thought of, and had spared no expense to try and have the nuisance abated, but that all his exertions were useless. I then begged him to send down and purchase a few loads of peat charcoal, which were selling at the market; and having told the master how to employ it, the suggestion was at once adopted, and though the material was not of the best description, nor “ recently prepared,” in a very few hours the most delicate and practiced nose could not have detected the slightest offensive odour. Since then the master, with very praiseworthy attention, has had a large pit of the charcoal prepared every week, and by its occasional use through the grating of the sewers, and by sprinkling it over the nightsoil in the privies, the workhouse is, as far as entire freedom from every noxious and offensive effluvinm, a model to every other in the kingdom. In every respect the results have been most satisfactory. Instead of paying from five to ten pounds, every half year, for having the privies cleansed; and having itself and the whole surrounding neighbourhood at the same time poisoned for weeks by the intolerable stench ; the establishment has that task now performed by the paupers, without the slightest reluctance on their part;—and the contents of the sewers, cess-pools, and privies are now collected into inodorous and innoxious heaps, or mixed with the other refuse of the workhouse until removed by the contractor; which, before, he absolutely refused doing, but which he now considers the most valuable portion of what he contracted for.

Also, adding significant amounts of dirt on top of the daily deposits would completely cover them, so flies would not likely be an issue either. Ov course you could tweak the amount of soil added in order to either improve more soil in a shorter time, or to make the latrine last longer to the end of digging less. I’m seeing this more as a way to improve a lot of soil at this point, so thinking of finding the minimum amount of poo to maximum amount of dirt and charcoal added back, while still ensuring good results.

So, one issue with burying charcoal in the soil is that it is a nutrient magnet. The first time I did it, the lettuce I planted afterward failed to thrive. It was pretty bad, I mean it barely grew and produced nothing really edible. The most recent garden bed I amended with charcoal, I added a lot of chicken manure and compost teas to as it was being dug in, in order to charge the charcoal up so it wouldn’t just suck everything up leaving nothing for the plants. That bed is doing well in it’s first year. Once it’s charged up, this property of charcoal to catch and hold nutrients becomes a benefit rather than a liability, possibly the most important property of biochar, but it must be charged somehow. The latrine system should provide a nutrient rich environment to charge the charcoal up as it’s added. I would probably add stuff in this order:

poo

ash

charcoal

amendments

dirt

organic matter (if added at all, probably a little forest duff at least, if just for innoculation with diverse soil organisms).

The current outhouse structure can be carried by 4 people or rolled on logs by two, but it is far too heavy and awkward to be moved frequently by one person. I’m thinking that a more tent like arrangement would be better suited to my trench latrine plan. I though originally of some rails that the covering slid on, but I think that a more simple and elegant solution is needed. I’m thinking for my style a couple of planks with a space in the middle to use as a squatting toilet and a light frame covered with a section of plastic billboard tarp could be plenty cozy enough. The tent covering would need good anchorage from winds... maybe sand bags or cinder blocks which bungee to the frame? We’ll see. No need for a door most of the time, depending on the site I guess, but an old sheet should work okay.

The great majority of us are wasting the nutrients we excrete. This state of affairs makes not a bit of sense at all. For homesteaders, finding some way to utilize the nutrients that are leaving our bodies seems like it should be something of a priority. We can’t afford to hemorrhage nutrients out of our living systems and we shouldn’t even if we can re-import them from somewhere else. While saving urine to use as a fertilizer will catch the vast majority of the useful plant nutrients leaving your bodies, and is a great first start, doodie also has a lot of good stuff that can be turned to advantage. This system seems very promising to me. It’s going to be too much work for some people, but for tough and scrappy homesteader types and less “developed” cultures and areas, it is probably fine. The prospect of the opportunity to create super soil zones by utilizing immediately available resources and a trickle of labor from already daily activity, gets me all hot and bothered and would light a fire under my ass to go start digging if said ass wasn't glued to a chair most of the time. I mean that shit is exciting people!

My proposal is really for a system which modifies the soil to quite a depth, but I suppose it could be used in a shallower form too. For a system that required more upfront investment, but less labor over all, the ecosan system with charcoal added to the ash might be a good way to go. Briefly, the Ecosan system uses two pits. Urine is diverted out of the system and collected in containers for direct use. Each time a solid deposit is made, a handful of ash is added to cover it, help dry it out, and alkalize it, all of which kills off microorganisms. The collection chambers are ventilated to encourage drying. Once one pit is “full” it is closed off to dry completely, and the other side is used. By the time pit two is full, six months or more later, pit one is completely dry and innocuous. If charcoal was added, it would pre-charge the char as well and the whole lot could be pulverized as a very rich, fertilizer for use primarily on annual crops.

Here at Turkeysong I could see running both systems eventually. I’m pretty tough, and am used to inconvenience from years of re-training my entitlement set points. I'll spare you the details, but trust me, I have gotten through the worst of times with the most inconvenient toilet and living situations, like no toilets at all and extremely ill, rain or shine, day and night. But, um, honestly, tough or not, I’d rather sometimes have a close outhouse to visit! Inconvenience isn’t the goal or noble in and of itself. Sometimes simple solutions are still the most elegant ones though and being constantly besieged by convenience can make us into weak and whiny people.

I’m pretty opposed to the idea of indoor bathrooms. Digging little holes in the forest or crapping in a trench might seem crude, but pooping in your house just seems plain uncivilized to me. I could see both the Ecosan and trench systems eventually operating simultaneously in a place like this. The cozy, luxurious Ecosan, (maybe with a door, or a light and some reading material even! How about a stereo, wide screen t.v... wifi...) close to sleeping quarters for late nights and rainy days, and the biochar trench latrine for the rest of the time, or for special soil improvement projects.

I hope this idea will appeal to someone enough to try it out and we can see what the profits and pitfalls might be. Obviously, making a bunch of charcoal is in order, quite a lot actually. The good thing is that once it's made, it keeps forever. I managed this past winter and spring to experiment a little with the top down burn pile and pit methods of charcoal production. Both are easy and accessible and can be used with random scrappy brush. I’ll leave you with the super condensed version of both, but stay tuned for more on those in future posts or videos.

Top down piles: Pile brush in a tall narrow pile. A tall narrow pile is more work, but it burns better than a mound shaped pile. Light from the top which produces way less smoke. Throw unburned pieces from the outside into the center as burning progresses. When most of the wood is charred and no longer flaming, douse with water.

Top down pile, ready to light as soon as rains start. See this pile burn here!

Pit: dig a pit with sloping sides. For long wood, dig a long pit so you don’t have to cut the wood. start a long narrow fire in the bottom. Add wood in layers. When burned down and not producing much flame, add a layer. try to cover the layer below well, but each layer should be only about one stick thick, not piled up. this system doesn't work very well with very tangly torturous type brush. Conifer limbs with the needles on are fine, but oak brush with branches pointing in every direction and taking up a lot of space in every direction needs to be broken down a bit. This system works by smothering the previous layers with new fuel. Just remember to try to have the new layer close down on the top of the old one to smother the coals below so they don't continue to burn. When very little flame is left and the pit is full, douse with water.

Burning charcoal in a trench. There is a trench, this is the end of the burn when it's full of charcoal. Video here.

I think the pit is probably more efficient in the wood used to charcoal produced ratio than the top down pile style--- but it seems to require a little more work and attention too. I’m not really sure yet. In both cases, don’t wait for every single piece of wood to be charred before extinguishing. You will end up with some un-charred wood, but you can always re-burn it. If you wait for every single piece to be charred before extinguishing it, the wood that is already burned down to coals is rapidly turning to ash, effectively reducing the total charcoal yield.

I’m somewhat annoyed with myself for not "having my shit together" already. But, when we have to always be pioneering new ideas and systems, it’s not always easy to get it together, and I have a lot of challenges to face so I'm cutting myself some slack. I’m convinced that urine diversion is the first step and anyone who has hung around this blog much knows I just won’t shut up about that. Next, something like the ecosan system and/or a system like I’ve just proposed that amends soil as it goes along, should make maximum use of our leavings. And that should be the goal. We are so fixated on disposal, and the idea of excrement being a valuable resource is so totally foreign, that it is often difficult to find language that can really get across the way we should truly be thinking about the issue. Like I said, it makes no goddamn sense to extract the very essence of the soil, that which plants make their bodies with, and then throw it away. Not only should homies like us be building our infrastructure around a new paradigm, but as a society, we should be thinking toward decommissioning our old systems and implementing new ones that honor our daily discharges as the very valuable resources they are. My trench latrine will certainly not appeal to the timid, but it can’t be that hard to come up with a design that tops the current practice of pissing and shitting in a ceramic bowl of water in the house! Like omg, that shit is nasty. And said bowl has to be cleaned by some unfortunate person, like ewwwwww.... If we can put people on the moon as they say...

Summary:

*Dig a trench or pit, up to a meter deep.

*Use a light moveable cover.

*I'll probably use planks for a floor with a space left open to squat over. An elegant solution and highly flexible.

*Add charcoal, dirt and/or other nutrients and amendments with each deposit. shoot for 15% and up of charcoal if possible.

*Find a poo to dirt and charcoal ratio that makes maximum use of droppings and fills the hole quickly.

*If a trench is used, expand the trench as the previous section is filled up.

*Be stoked that you've done something agricultural that may actually last for a really long time, unlike standard impermanent soil improvements.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YV-1To9DkJQ

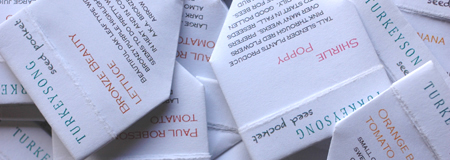

Turkeysong Origami Seed Pockets Video Goes Live!

At some point a year or two ago, I had to come up with a folded packet/envelope design so I could give away the seeds that I save at farmer's markets, scion exchanges and places like that. I like giving away seeds. I often give away too many and end up kicking myself, but it is so compelling for some reason! The first thing that came to mind was those little paper packets called bindles that cocaine used to come in back in the 80's. Learning to fold bindles was about the only real good I ever got out the stuff. Cocaine was around a lot back then, but I had little use for it. I think I was more interested in the bindles than the coke. I did so little of it that I couldn't remember how to make those little folded paper bindles almost 30 years later. So, anyway, no bindles. I had to improvise. I'm not sure why I didn't just look for instructions on the internet, but I'm glad I didn't.

I had recently come up with an origami container for roasted baynuts that was pretty nifty, so I was emboldened to the task and began folding away fearlessly. I already knew I wanted it to be a quarter sheet or smaller. The result after a few minor adjustments is this origami dubbed "seed pocket" for obvious reasons. It came out with some neat unexpected features. The back tabs lock together in a really neat way to keep the packet closed. If stuffed super full it may open at the back (though it's still unlikely to spill seeds) but then you can just make a larger one out of a full sheet instead of a quarter sheet. I prefer to tear the paper after creasing, because the torn edges appear under the title, which looks cool and more handcrafted-like. there are also a lot of squares and half square triangles formed, so the proportions are pleasing to an OCDish person fixated on symmetry, like me. These are very seed tight and unlikely to leak even small seeds like poppy. In fact, I just packed up some tiny shirlie poppy seeds last night. I'm not so sure about super teeny weeny tiny seeds like tobacco and lobelia, but otherwise, they're pretty dang tight!

I've got one laid out in adobe illustrator for each of the seed varieties that I save regularly, with names, short descriptions and a nudge in the direction of my blog to pick up web traffic. They serve a little like business cards and are very popular. It's a lot of folding, but I actually like folding them while watching a movie or just thinking about stuff. It's sort of addictive. I've probably folded thousands by now.

I'm making the Adobe Illustrator template available as a downloadable file, so if you have access to adobe illustrator, you can leave the layout (which took a helluva long time to get right, so be careful messing with it!) and just change the text and fonts to suit your own farm name, variety names, descriptions and such. You may need to download the fonts I used if you want to keep them (Copperplate gothic light, Century old style standard, Cambria and Chalkduster). Putting some text on the inside of the packet is a possibility too, and I may add seed saving instructions for each vegetable eventually if I can get my stupid printer to stop eating so much paper. I kept it pretty simple, but one could add all kinds of things- colors, pictures, gardening quotes, fold lines...

This template is for four small seed pockets per 8.5 x 11 inch sheet. I haven't made a full sheet template, but I do use the same origami design for making an occasional large seed packet. If you use the template, I'd appreciate the small favor of leaving the blip on the underside of the flap so people can find the template and this post and my blog. Thanks!

So, save some seeds this year! If you haven't saved seed before, tomatoes are an easy place to start. They rarely cross with each other. Just take a non-hybrid tomato that you like, squish the seeds into a bowl, let it ferment for a day or two to dissolve the pulp, wash and drain several times to clean the seeds, and dry on a piece of paper in the shade until thoroughly dry.

This is the first video of what I hope will be many. Big thanks to blog reader lars for hooking me up with a video camera! Thanks dude!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ioub3uAsfSU

And don't miss my one other youtube video ever, the epic guinea pig munch off!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vGqF63c6LZw

Manure Mats

“EDIT: I’m not sure how long ago I posted this, but I’m still totally into this method. It has worked awesome for me in many ways. Also, having just re-read this long post, I think it’s great. I feel always to need to be apologetic about discussing things beyond a “do this in these easy steps” sort of approach. That is because the modern mindset is increasingly about the short version of everything and it is only getting worse in the digital age. Successful homesteading and gardening is about adaptation, not paint by numbers.”

Preface-like paragraph: I have, over many years and with a lot of intention, slowly come to see the world around me as a sort of resource-scape, that is, as a world of potential resources. This can extend to people and ideas as well as physical objects and also phenomena of energy, like wind, or sun, or the action of an animal. Having made a pretty intense study of primitive technology as well as of other subsistence paradigms, I’ve been impressed deeply by the fact that different groups of people, given similar environments, or even the exact same environment, will do completely different things there and live very different lives. While we are guided by our environments, we are also very much guided by our cultural influences and what we know, or just as importantly what we think we know is and is not possible.

So? As a result of this perspective of resource consciousness, I tend to walk around constantly looking for unseen or undervalued potential that could be harnessed to make life better, more sustainable, or to make work more efficient and certainly a little just to keep myself entertained! While this view has resulted in way more ideas than I have energy to experiment with or turn into functional realities, having that view does serve me decently well sometimes. I’ve noticed in the garden that there are numerous resources that are underexploited and can be micromanaged into great usefulness. One of my main influences in this area is Farmers of Forty Centuries. It is a long, boring ass, pedantic book from the 40’s that is probably a good 100 pages longer than it needed to be. It is worth reading though for a few specific items of farming practice and, more importantly, the broader message of what can be done with resources that we might not even stop to think are useful in our modern society where views of work and resources are extremely skewed away from traditional ones. The picture painted by that book makes any western gardening I’ve ever seen seem absurdly sloppy and wasteful. We are spoiled, and that’s great in it’s way, but it blinds us to the potential around us when compared with the Asian cultures in that book who really had to figure out how to make use of every resource in the most efficient way they could come up with in order to survive their own high populations. Necessity is indeed the mother of invention. I just wanted to drop those general ideas on you before I start this specific story, because it’s somewhat relevant.

This way to geekage ---> There is a long path to get to the actual subject. But bear with me. The sights along the path set the context and this post isn’t actually just about one idea. There is an idea, but it could be summed up in a few paragraphs. But that idea evolved in a context which has specific real or perceived problems, and that context has other lessons and provides a framework for learning about the world we live in (or at least the one I live in!). And, there is more to glean than the end point idea, which after all is not an end point at all, but just part of a long evolution. It may be a good idea for me, while it may fail you utterly or be totally irrelevant to your life and work; but if we view it in a larger picture, we have more places to go from here and may find modifications, or other uses and ideas branching off of this one. So hang with me if you want to, or just go read the last couple of paragraphs.

The Pee era. I used urine as a fertilizer for over 10 years. At first I used it cautiously, but as my unfounded fears about the idea dissolved, it became the staple fertilizer. Suffice to say that it basically solved my fertilizing problems. A while back, doing farmer’s markets finally started to become a feasible reality. I can’t plan well enough to grow just how much I need, so there is always a lot of surplus, and it’s great to get something back for my work and prevent “waste”. But in order to start going to market, I had to stop using pee as a fertilizer for both ethical and presumably legal reasons, and so began a transition period.

Transition. Pee really had solved almost all of my fertilizing needs. The use of compost has always continued, but differently than I had used it up until moving to Turkeysong (more on that below). The compost is very useful as a fertilizer, but I in no way produced enough from kitchen and garden scraps here to keep everything in a large garden growing really well. Compost is an okay fertilizer, but rarely high enough in nitrogen to keep things really pushing vigorously through the season. Thus the pee. It was a semi-closed system and I learned a lot. But, with the new no pee garden, I now had a fertilizer problem. Chickens made a showing at a fortuitous time and there is now a thriving flock that is reproducing itself. They eat the food waste from the kitchen of a local hot springs resort along with whatever they can scratch up around the place. They poop a LOT! Most of it ends up all over the yard, and many times a day right on the door step. They are super poopers! Most of it dries up in the yard somewhere, but the new chicken coop has a screened false floor with a solid floor below that. So, the droppings, after falling through to the lower floor, which is well ventilated, dry out and can be accessed from both ends by scraping them out. It’s a pretty good system. No climbing into a crowded coop to awkwardly shovel out caked bedding from under the roost while breathing poo and feather dust. Yeah, right? Most people with chickens have been there and would rather not have been. Lately I’ve been feeding them their buckets of food scraps in the evening, so that they digest and poop all night in the coop. That’s the idea anyway.

The PoopCoop! This coop was my idea, designed and built by tonia. It has a 1x2 inch galvanized wire mesh floor and a wooden subfloor. The subfloor is well ventilated and can be accessed for poo removal from the front and back. There are boards screwed on the access points to keep the chickens from getting in there scratching around for bugs. I would make the access slots a little taller for easier access, maybe with doors instead of boards screwed on. Otherwise, it works pretty great. Make sure you orient the wire and the boards on the drying floor in the right direction for easy scrapping, otherwise you get a washboard effect.

Chicken Pee. So, I now have a fertilizer supply that I can use on my market garden. The chickens collect and concentrate nutrients into a reasonably convenient form and I can collect a bunch of it from the coop. Chickens are designed efficiently. They use the same hole for sex, egg laying, pooping and peeing, everything except eating and breathing. But of course they don’t actually pee at all. We pee out the vast majority of our nutrients, but with chickens it all comes out in one package. So, I really am still using pee, just dessicated chicken pee! I don’t have an endless supply, but I hope with careful use, and augmentation from other resources I have access to, I won’t have to import much of anything to keep the garden going; which would make me happy since I like to keep imports low. I’m also very hesitant to bring in manures from the outside as they almost inevitably have some seeds of weeds which I don’t yet have here in this somewhat remote location.

No dig, dig? Another part of this whole picture is that when I moved to Turkeysong, I also stopped regular digging of the garden beds. I quit digging because I was terrified of a small, root eating organism known as symphylans which had devastated my last garden. These little suckers are a true plague. Word on the street was that the best way to encourage the tiny centipede-like bastards was having high soil organic matter to feed them, along with a loose soil structure so they can move around easily. Well fuck me runnin’ backwards, those two things combined just happen to be the two holy grails of organic gardening dogma that I’d been trying to achieve for years! Take home point, I didn’t want to dig in tons of undigested organic matter anymore. I tried that in my last garden when I experimented with seriously adopting the bio-intensive method, which means lots of deep digging, and digging in lots of compost. It didn’t work out so well. The symphylans population exploded. It was also (biointensive propaganda notwithstanding) a ridiculous amount of work. Your mileage may vary.

The evils of soil crusting >:( Now this bit is really important to my story. Soil crusting has always been one of my major problems in gardening. When the soil structure is damaged by watering and cultivation, it crusts over when watered or rained on, sealing off the surface and preventing the exchange of air. Crusting also forms a barrier to water penetration making watering, inefficient and wasteful due to run off. Sometimes it seems to make watering almost impossible, yet the more you water, the more crusting occurs, drats! Furthermore, compacted soil is a pathway for water to travel up from below and be evaporated back into the atmosphere. It’s basically like a wick for removing water from the soil. These problems are really frustrating and have been an issue in virtually every soil I’ve worked with, from sandy loam to clay. Honestly, I’m surprised soil crusting doesn’t get more play. It is a key problem in gardening.

Organic matter my ass. One commonly proffered solution to crusting is to increase soil organic matter content. I’m going to go out on a limb here and say that’s bollocks. It’s not that it doesn’t work at all (you’ll see that it actually works for me presently), but I’ve never seen it work well when digging compost in, except when the organic matter content is quite high, which really entails digging in an enormous amount of compost... enter symphylans. That also usually means basically buying or composting a whole shit ton of something to build a soil that has a huge proportion of organic matter. Otherwise, whenever you dig the soil you pull up more low organic matter subsoil onto the bed surface, and you’re back to crusting. That’s my experience anyway. Also, exposing organic matter to oxygen allegedly increases oxidation ultimately lowering organic matter, so that's a losing battle.

Cultivation, is it really evil? The other solution to soil crusting is good old cultivation. That’s the typical solution and seems almost essential in large scale agriculture. Cultivation loosens the soil to break capillary action, stopping evaporation. It can also kill weeds and allow water to penetrate the surface. Problem is, the more you cultivate the more you smash the soil into fine particles (dust), destroying the structure, and the more easily it crusts again when watered. So, you just have to keep doing it. You ideally want the top 4to 6 inches or so of soil to be almost dust-like for the best moisture saving effect. Negative press aside, it’s not always the evil system it’s sometimes made out to be and has a place. I used regular cultivation the first year I was here and I was amazed at how far I could go between waterings if the soil was re-cultivated as soon a possible after watering and without fail. It was one of the best gardens I ever grew, though not just because of thorough cultivation. I’m not sure I’m done with cultivation gardening, and I just see it as a tool in the tool kit, though I have to admit, it seems somewhat less than friendly to the concept of soil building and probably a somewhat shoddy way to treat the land longterm.

This first year garden at Turkeysong was under surface cultivation. I returned from a several day trip with a friend during a multi-day, over 100 degrees f, heat wave and he was astounded at my perky butter lettuce which had been watered and cultivated just before leaving. This intervention only solves crusting if you do it soon after watering, every single time.

Mulch is god! I knew I had to solve the problem of soil crusting, and if I didn’t want to cultivate extensively, that left mulch. Mulch is GOD! Right? Just ask Ruth Stout, or a young and enthusiastic mulcher. Get in with a real mulch enthusiast with limited experience, and you’d think all your problems will be solved forever and that we are all just a few bales of straw and some lawn clippings and leaves away from solving all the problems of horticulture and maybe beyond. Combine mulching with gogi berries, biochar, blue green algae, perennial vegetables, and ducks and there’s no stopping perfect plant and human health and “no work” food production! Ok, I’m being a dick, but we deserve it. It is so tempting to see something as having the real potential to just sort of “fix” everything. I know well enough, because I’ve been that eager inexperienced mulch promoter. Most of these fairytale happy ending stories we tell ourselves have at least a grain of truth, and often much to offer us if we can actually see, or more often after we inevitably see, through experience, the limitations and pitfalls that are not visible in the theoretical realm, and which we don’t really want to see anyway. Mulch is not god. It changes the landscape in ways that are often very useful to us and to the health of the soil. It’s effects are sometimes super awesome. I’m a big fan and semi-regular practitioner, but some of those changes can conflict with our food producing and land care goals. Creating habitat for voles and insects came to my mind as particular problems in considering deep mulching for my garden. It’s bad enough in any garden where there is always some habitat for insects. Deep coarse mulch can create a veritable pest metropolis from which an army of insects can march a whole few inches to chow down on your carrot seedlings, or in which voles can find the rodent equivalent of mcdonaldsplayland to move into, complete with a food supply... weee! I do use deep mulch, and what I might call semi-deep mulch, here and there, but experience had already taught me that if I used it in the entire garden, I would have considerable negative issues to deal with. That may vary by environment, but enough said there. I’d also be out collecting the stuff all the time, because it takes a ton of material to do deep mulches in a large garden. That reason alone is enough to scrap the idea. No thanks Ruth.

Works pretty good. My eventual solution, partly influenced by some no dig gardener/writers, was to use finished compost as a mulch. Since I would be composting food waste and garden stuff anyway, and didn’t want to dig it in, this seemed like a good solution. I’ve used all my compost on the surface of the beds for something like 6 or 7 years now. It works pretty good for me. I don’t have as much as I want. Each time I plant something new it gets a sprinkle of compost, usually almost enough to cover the bed surface visually, so under 1/2 inch thick. Some washes away with runoff when I water, and I still get quite a bit of crusting. But overall, for my system and my soil, gardening style, and so on... it’s been pretty good. I do have to cultivate some when crusting gets bad enough in an area (usually due to running short on compost, loss during watering, rodents helping me do some digging, or having had to dig the area recently for harvesting roots and weeding). I use a hula hoe (aka strap hoe, stirrup hoe, reciprocating hoe, scuffle hoe) for cultivating, generally trying to slice below the soil an inch or so leaving the top relatively undisturbed. I wish I had more compost, but I get by. I sift it through a half inch screen and throw all the big stuff back into the next batch. That puts a lot of half digested material on the beds, and I prefer it that way, because larger bits of stuff cover the soil better. I’m kind of bummed if the compost gets so finished that most of it is very fine and not recognizable as pieces of plants and stuff, because it doesn’t do the main job I need it to as well as it would if it was in bigger pieces, and it washes away more easily. I also sometimes use coffee grounds picked up at a coffee shop in town, which adds to the effect and contributes quite a bit of nitrogen.

Soil layers. The compost makes quite a difference in crusting. One thing I’ve noticed, is that since I don’t dig regularly, the organic matter stays in the top layer of soil. It doesn’t just stay on the surface. Worms come up and grab pieces pulling them underground. moles voles and gophers do plenty of digging for me and I have to plant, harvest and occasionally cultivate. But a lot of it stays in the top inch or two of soil. I’ve noticed that even when I do get crusting, it is not as bad as it could be, and is somehow still permeable to water and air relative to the crust that forms on a dug soil. That’s because this top layer is quite high in organic matter, which builds up over the years. This effect simulates a natural soil profile more closely than a cultivated soil does.

Artificial, but how artificial?But, a garden is not a natural environment! My symphylans problem in my previous garden highlighted that fact. What I am after is an artificial environment that can pump up the plants to realize the potential bred into them through the ages to grow plump and juicy. But, I want that effect, without upsetting the balance so much that I create some unintentional problem that is going to bite me in the ass (in a bad way ;). Mulching with compost seemed like a good solution. I really could use more of it. I’d like to make more compost. Materials are abundant. I live on 40 acres of mostly forest, and organic materials supply is not an issue! There is also plenty of seed-free green grass to collect in season. Any farmer out of that super boring book Farmers of Forty Centuries that I mentioned earlier would be appalled at the lack of use of the resources available to me. But alas, energy is in short supply and I do have other things I want to do, like compulsively writing blog posts for hours and hours. Besides, like I said, it works pretty good the way I’ve been doing it.

Chicken pee tea. So, were getting close to my simple, but really cool idea (close is relative). Since I don’t dig the garden beds (see footnote *) my options are to use my chicken manure on top of the beds, or use it as a tea. Both work well and have advantages, and I’m using both currently. I’ve been sifting the dry chicken manure and applying the fine siftings to the beds. That works nicely and contributes to the prevention of soil crusting, while building organic matter in the top layer of soil as long as I don't dig. As the bed is watered and bugs and worms and microbes do their work, the nutrients leach into the soil over time. Direct application has it’s advantages, but manure tea also has advantages. Being full of soluble nutrients, manure tea gives a quick boost when it’s wanted. It can also be applied very evenly for efficient use. Using soluble fertilizers in general provides the potential to keep plants growing strongly with regular applications through the growing season. Soluble v.s. non soluble fertilizers is a whole can of worms, but I like to use both and it works for me.

Tree mats. I make manure tea by soaking the poo in water and then straining it out. The tea is diluted and then applied straight to the beds/plants and usually watered in immediately. Applications of course stop some time before food is harvested. I usually leach the manure several times over the course of some weeks before it is pretty spent. When I’m done I have this wad of left over half digested manure. I used to throw it in the compost. I had an idea a while back. I’m not sure if it’s at all practical for home production, but I have no doubt that the actual product would be pretty awesome once made. The idea was to make a sort of paper mat out of manure and pulped up cardboard and other fiber stuff like that. It would be a large, thick, probably circular mat for mulching trees. You could incorporate all kinds of fertilizers and nutrients and nutrient containing stuff in there like seaweed, bone meal, etc, which would leach out and feed the tree over the years. It would also provide a moisture conserving mulch and eliminate competition for a few years if it was thick and durable enough, which would really be it's main use. It could be a good use for all that cardboard and paper filling dumpsters everywhere. Practical to make or not, I’m convinced that it would be completely awesome, solving a bunch of problems in one item and allowing the quick establishment of trees with very little work and in many cases without watering, even in our dry summers.

We made it! It occurred to me at some point that I could make tree matts with my manure left over from making tea, but of course it’s probably too involved to actually do here practically speaking. I would need an outboard motor or the like to mix it all up. Besides, there isn’t enough manure. So, I just mixed the chicken poo sludge with water to form a sort of slurry and dumped it out onto a bed. With a little watering, the half digested slurry spread out pretty evenly, forming a solid mat of slow release fertilizing mulch! It’s true that much of the nutriment has been leached out, but some remains too and much of it locked into the undissolved organic matter. This method covers the soil almost completely if applied generously enough. It drastically slows evaporation compared to a compost mulch only bed, but won’t wash off at all. It provides food for worms and other bug dudes who work near the soil surface, opening the soil texture to allow penetration of air and water. It feeds the plants slowly, and also initially through a dilute, but still very substantial manure tea effect. It of course protects the soil from crusting due to watering and rain. And, it provides organic matter as it breaks down into fine bits and is slowly incorporated into the top layer of the soil. It uses the product of a process that is already underway, so there is no “extra” preparation work except stirring. It is easy to apply. The effect is durable; it’s thick enough to provide a substantial effect, but not so thick as to make deep multilayered habitat for an army of insects; so, it seems a good compromise between creating bug habitat and thoroughly covering the soil. It just seems pretty awesome! It doesn’t work for everything. I don’t use it on small seedlings. I couldn’t use it on carrots because it would just bury them. But it works great for larger plants such as squash, tomatoes, peppers, cole crops etc... and it seems ideal for onions and leeks. Burning plants is a non issue since it is already pretty well leached by the time I’m using it. I’ve been playing with this a bit for a few years, but now that I have to use a lot of manure tea, and have a lot of manure, I have more of the slurry to use and have applied much more this year. I’m pretty sold on the idea, though still have an eye open to the possibility of unforeseen issues cropping up. I’ve also used horse manure, which worked great, maybe even better because of all the pieces of stringy fiber in it.

The beginning of the end. Like I said, this doesn’t have to be an end to the evolution of ideas. Our accumulating knowledge, our input from other people, our observations of all kinds of things, an ever deepening understanding of the habitat we live in and modify, an ever increasing awareness of the resources available to us and the idea that there are more that we haven’t yet recognized, and maybe most of all, an awareness of the utility and beauty of the potential that exists to combine all these things into functional systems, can all come together to form a foundation for success in adapting to the places we’ve landed in and which eventually, through close association, come to be home to us. These ideas are very much at odds to most of what passes for modern life. Creatives, entrepreneurs, and many others do use this kind of thinking in the habitat of modern civilization, but many have no need in the paint by numbers lifestyles made available to us by industrial life. That doesn’t fly so well when you are trying to bring forth some kind of living on the land from available resources. Our lands and ecologies are unique and changing entities. They have their own characters which change with the seasons, over time, and with our inputs and the consequences of our habitation, intended or otherwise. This post has been largely an excuse to talk about those ideas and the specific ideas and things that I do surrounding, and leading up to this one simple expedient, which solves some problems that I face. Should you run out and find some manure and start using manure tea so you can have some slushy poop to dump on your garden beds so that you don’t have to dig and will have awesome soil that brings forth giant leeks flushed with the color of life giving nutrients? I don’t know. Maybe. Okay, probably ;), but that’s not really the point. The point is more that we can benefit from being aware that there are almost limitless possibilities, and be open to the evolution of integrated ideas that can lead to systems that work for our goals, lifestyles and resources.

The end of the end. I hope someone made it all the way through, and that this rather long discussion has been of some use in promoting, or reinforcing, some useful general concepts as well as offering some more directly practical information that might be of use to you and your situation. Tips and tricks are great, but I’m more and more convinced that our broader philosophies and beliefs can be the real impetus for our “success”. They form a foundation for our goals and inspiration, the choices that spring forth from the values we decide that we want to embody, and ultimately the specific things we manifest. They even largely define what we think success even IS. Specific systems can be shared out among us, but life on the homestead is not paint by numbers and a particular idea or method might serve as much or more as a stepping off place or stimulant of new ideas than something to be directly adopted.

(* footnote re: not digging beds: I rarely dig beds, but I’m not religious about it or anything. If a bed gets compacted I dig it, and I am trying a little digging prep for carrot beds to see if I can get the uniform roots the farmer’s market customers want (edit: It didn’t help. No real difference between carrots in dug and undug soil here). I do really try to avoid actually turning the soil over, unless I’m trying to work in some permanent amendment very deep, like when digging in biochar. I know people who are terrified of digging or turning the soil at all though, which just seems silly.)

And a Frankentree in Every Garage

If I were president, the essay assignment goes when you’re in grade school. I remember thinking “but I don’t want to be president!” But... if I was, I don't think I'd promise a car in every garage, though I'd probably keep the chicken in every pot. When I moved here to Turkeysong, I had to decide what fruit varieties to grow. Inspired by friend and apple guru Freddy Menge, a scrappy young tree that was already here, was used as a framework to test out apple varieties. Before that it produced hard green apples. What started as an interest, grew into something like an obsession and the tree became more diverse every year starting with 25 or so varieties and ending now with about 140. My friend Spring dubbed it Frankentree because, at her house, that’s what they call anything cobbed together from odd parts. The name stuck. The term frankentree is also used for genetically modified tree varieties, but it has already taken off among apple collectors, so we'll just have to see who wins. And maybe someone searching for info about GMO fruit will run across our frankentrees and be ignited into constructive action instead of plunged into despair at how the world can be dumb enough that we take the risk of genetically engineering an apple just so it won't brown when cut.

Frankentrees are awesome! They may take a little attention to maintain, but the advantages are many. There are so many trees out there that provide too much fruit of one variety in too brief a period for the people that use them. Other trees just produce fruit that no one likes. These trees, if they are healthy enough and the form is not too wacky, are very valuable as a base to work from. A reasonably well formed healthy tree can come to yield nourishment in abundance, interest, variety, valuable information, and even self confidence and self reliance, over a long season.

This isn’t going to be a how to article, it’s more to kick you in the butt and get you started thinking and experimenting this year article. If you have a tree, or access to a tree that is not very exciting in the fruit department, why not try grafting on something new? Well, I’ll tell you why you should graft on something new, or actually more like somethings.

Apple trees are an ideal format in which to learn grafting and begin fruit collecting. Pears are a close second, and then plums. Apples are easy to graft, very useful, widely appreciated and there are many varieties to be had, thousands actually. They also are hard to beat in terms of seasonal length. I have very good to excellent eating apples from August to early February, and that is straight off the tree, not accounting for storage. You may not be able to get that in a very cold climate, but the season can still be quite long. The ability to have a long fruiting season is reason enough to make a frankentree, but there are many more motivations.

Frankentreeing will teach you something, and you can teach that to someone else. You’ll learn about different varieties of fruit, what their seasons are, what they taste like, whether they keep or not, and very probably their histories. You’ll learn the art of grafting, without which we would not have all these varieties of fruits in the first place. And you’ll learn what varieties do well in your area, which is extremely valuable.

You'll also end up as a keeper and preserver of variety, a sort of seed bank or scion repository that you can share out or trade from. No doubt some of those varieties will be very old. And old or not, more diversity in more places is assurance not only against permanent genetic loss, but also that diversity has a real place in our daily lives. We have to live our appreciation of variety and the romance of diversity in crops for it to be real and not just an abstract idea we picked up from a foodie book.

Multi-grafted trees are not only ornamental in their own strange way, but they’re also a great conversation piece, and a frankentree will make you look cool! Wait, screw that, if you make a frankentree, you are cool! Everyone who visits here loves frankentree!

You’ll very likely have more fruit on a frankentree. First of all, pollination will be great. Apples can self pollinate to a very small extent, but they really need pollen from other varieties in order to fruit. Your frankentree will be downright indecent in it’s public orgy of bees and pollen! But wait, there’s more! You’ll also get more fruit in the long run because you’ll inevitably end up with some that set fruit very readily and consistently, and some that avoid spring frost because they bloom late.

Your new skill is marketable as I’m finding out. How many people will pay you to make them a fruit tree that gives them four to six months of the most delicious apples adapted to your region? Let’s find out! I just did my first paying frankentree job (bride of frankentree) for my neighbors Dan and Leslie and they seem very pleased to try giving an old apple tree a makeover. It made good apples before, but it will make lots of different good apples now. I have another such job scheduled this spring too.

I’m a problem solver. I not only solve them, it order to be a good problem solver, I have to look for them constantly in everything. Just ask anyone who has had to live with me. So what’s the downside to a frankentree? There are very few really.

If the tree is too old and you have to cut down to large stubs, you could get some rot that will shorten the life of the tree. In many cases, that is not necessary though. I prefer to stay within cuts that are 3/4 inches and down, but you just have to weigh the value of the tree as it is and the value of it as a frankentree, or more usually the value of a certain form of the tree, because if it’s very overgrown, you’ll want to simplify the framework and probably bring the head down. That’s will make it easier to graft, maintain and harvest.

It takes time and energy. Sorry, but I see that as a good thing over all. It’s like saying it’s a lot of work. If you’re not totally stoked about making it happen, do something else. Otherwise, activity that gets you outside feeling interested, taking care of your own needs and building self reliance... that’s all up side!

You’ll have to maintain the tree a little more closely. Some varieties are really vigorous and grow large and some are small and weak, so you can sort of keep an eye out to check the big ones and maintain a little light for the weak. I lost sleep over that when I first started, but I didn’t need to, because it’s no big deal. You’ll also have to prune off some suckers here and there as the base tree sprouts a shoot once in a while. sometimes those shoots will be more vigorous than the grafts, almost like the tree would rather grow itself than be a frankentree, which makes sense. My guess is that the investment you have in the project will make you more interested in maintaining the tree well. Your personal investment means value to you. It’s.... well, personal.

You can introduce disease. The one that is most common is virus. It will cause the leaves of some varieties to turn into a mosaic of light and dark areas. It's not fatal and doesn't seem to affect most varieties here. I basically don't worry about it anymore. The affected leaves can become sun burned easily. Frankentree is infected and so are many of my other varieties. Probably many more than I know, since most show minimal to no symptoms.

That’s all I can think of. I may sound like a propaganda machine, but I want to be! That’s how stoked I am about the idea and my enthusiasm comes from the pleasure, interest and knowledge I’ve reaped from me experience in this realm, and the way I see people respond when they find out you can do this, or take the walk to the orchard to meet “frank”. I’ll hopefully be giving you more specific detailed resources for frankentreeing in the future. In the meantime, go to a scion exchange if there is one near you, or join the North American Scion exchange and trade by mail. You may not have much to trade now, but there are quite a few generous collectors out there, and once you get a few varieties, you can start trading. If you don’t know how to graft, check out the many youtube videos, and hopefully I’ll add one sometime as well. I’d even like to do a detailed video just on frankentrees to give you more specific information and tricks to increase your success rates in grafting. In the meantime, here are some basic ideas to keep in mind. And for you locals, remember, the Mendocino Permaculture group's scion and seed exchange is this weekend Feb 1st Saturday 9:00 am to 4:00 pm. It's free with free grafting classes and rootstock for sale. I'm teaching hands on grafting coaching after the main grafting lectures.

Keep the framework of the tree, but thin it out and bring it down in height and in toward the framework, especially if it’s poorly trained, neglected and rangy.

Try to make smaller cuts and graft into wood 3/4 inch and down when possible, but don’t graft to the outside of the tree. Try to graft in closer to large limbs. If you graft only to small outside wood, you’ll end up with a tree that grows out and out and the inside of the tree will all still be the original variety.

Learn cleft grafts. They are easy and good for grafting small sticks to large stubs, which is usually what you end up doing when reworking a tree.

Use grafting paint (“wax”) liberally (I use doc farwell's, hopefully it’s not too toxic :/). Use it to really seal the clefts left open after grafting, but also to paint the whole scion lightly. Painting the scion is helpful to keep moisture in until the graft heals and the tree can start sending moisture and food to the scion. You might have to paint the open ends of the clefts twice to make sure they are sealed well against rain infiltration. It's ok if a little wax gets into the cleft.

Keep your grafting knife sharp!

Use long scions of 6 to 9 buds or so. This will give you fruit sooner.

Thin the area near the graft of other shoots if possible. You want to direct growth energy into the new graft.

If apples form the first year, leave them! You don’t usually have to pull them off to favor growth like you do with a young tree, because the tree is driven by an established root system.

Don’t unwrap the grafts too early. The leafy shoot will act like a sail and can break the graft. Unwrap before the wood becomes constricted. If you are concerned, just re-wrap it till the end of the season.

When you unwrap them for good in the fall, paint the graft union with a thick coat of grafting paint so you can keep track of its location.

Always label! I use aluminum tags with copper, aluminum, or at least galvanized wire. soda cans cut with scissors work fine and sections of aluminum venetian blind strips and old aluminum printing press plates work great. Scratch the name in and write with pencil too.

So, if I’ve sparked your interest, just bust a move this year, even if it’s a small one. Get some scions from a neighbor or a local apple orchard and make a few grafts. You can wrap them tight with cut rubber band strips and paint them with thick latex paint so you don't have to invest in grafting supplies. You can use a utility (razor) knife or pocket knife if you don’t have a grafting knife. Practice on prunings a little until you can make flat cuts and grafts seem to fit pretty well. You’ll learn something and if your few grafts take, you’ll have confidence to move forward. Maybe I need to start a career as a motivational speaker. Are you stoked yet!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QgXObaM9i2Q

Sloping Pit Charcoal Kiln and Agave Roasting

In the comments on the biochar experiment post, Lars mentioned Japanese cone kilns. I checked them out on Kelpie’s cool blog, Green Your Head and they do indeed look way cool. Although slapping a crude one together out of sheet metal would probably be pretty easy, Lars had just simply dug a pit in the same shape. I tried Lar's pit idea the other day, burned some charcoal in it, and learned a few things that I want to pass on. This is slightly premature compared to most of my post, which are typically backed by a bit more experience and contemplation, but I'd like to get this idea out there more. There is very little posted about it anywhere on the net, but it seems very promising, accessible and meets a lot of criteria for a good charcoal production system with very little effort.

In the comments on the biochar experiment post, Lars mentioned Japanese cone kilns. I checked them out on Kelpie’s cool blog, Green Your Head and they do indeed look way cool. Although slapping a crude one together out of sheet metal would probably be pretty easy, Lars had just simply dug a pit in the same shape. I tried Lar's pit idea the other day, burned some charcoal in it, and learned a few things that I want to pass on. This is slightly premature compared to most of my post, which are typically backed by a bit more experience and contemplation, but I'd like to get this idea out there more. There is very little posted about it anywhere on the net, but it seems very promising, accessible and meets a lot of criteria for a good charcoal production system with very little effort.

Part one. Sage, Agave and fishes (which have little to do with charcoal production.) If you are interested in burning charcoal and have a short attention span from internet overstimulation, skip ahead!

When I was in my 20’s I spent a lot of time backpacking out of Big Sur, on the coast of Central California. One of the common plants is Black Sage, White Sage’s little known, and much more potent sibling. I've always loved Black Sage and much prefer burning it to the white. When I moved here, I got some cuttings from someone and rooted them so I could have it around me. The scent still evokes a lot of fond memories from those good times out in the mountains. At the time, I lived in the Santa Cruz mountains and used to pick Black Sage and tie it into smudges. I now have quite a few plants growing, and tying Black Sage smudge sticks is one of many crafty cottage industry occupations that help bring in a little income around here. Most sage bundles are tied with cotton thread, wrapped in a spiral. That was way too domesticated for me back then, so I tied mine off with another plant I harvested in the Big Sur area, Yucca.

When I’d go out backpacking, I’d always harvest some yucca leaves on the way in to camp, pound them on a log by the river, and wash them clean of pulp to extract the long fibers. I’d twist those fibers into a cord, attach that cord to a stick, add a couple feet of fishing line on the end. The hook was nearly always a crude fishing fly I'd make by wrapping on whatever bits of feathers or fur I spotted on the hike in. My fishing kit fit in a tiny pouch, and that’s all I had to carry. My crude makeshift fishing rig worked awesome! Wow did those fish bite. Anything that remotely resembled a bug in the water got hit. That is elegance. extremely effective, low input, low cost, less junk to carry, connects me with the environment, builds skills, very little landfill material. Anyhoo, I always brought out some extra fiber or yucca leaves with me when I eventually made my way back to civilization, and ended up using yucca to tie up my sage bundles. The practice stuck.

There are several ways to process yucca. You can pound it fresh with a wood mallet on a smooth log and repeatedly wash and scrape it. (the pulp is soapy, so you can wash your clothes or dishes while you’re at it.) The pulp is somewhat tenacious though, so it’s easier to clean off if it is softened by either cooking it, or rotting in water in a process known as retting. Retting in water is pretty easy, but it takes a long time, and boy does it stink! The fibers don’t absorb the smell at all, but hands sure do. If left soaking too long, the fibers are also attacked by bacteria and weakened.

Up around these parts, there isn’t any yucca, but my neighbor Rob grows a lot of Agave americana, a large plant related to yucca which is also used to make tequilla. Agave americana is not the best agave species for fiber, but it is decent and good enough for tying sage bundles. I recently harvested some leaves over at Robs garden, an impressive meandering wild affair built up on a bare skim of soil over a serpentine rock outcrop and consisting only of the toughest most drought resistant plants. I wanted to bake the leaves because the last batch I tried to ret didn’t work out that great, and it’s winter so it could take months to ret a leaf that is 2 to 3 inches thick in some sections.

Ok, on to the charcoal kiln: I couldn’t just build a cone kiln. As soon as I saw the shape of the cone, I knew I’d be spending a lot of time cutting wood to fit it. That is a problem with many charcoal making apparatus. Fuel sometimes has to be reduced to a certain size. I figured that the principal of the Japanese cone kiln ought to work just as well (and actually better for my purposes) if the shape were longer. With a longer kiln pit, much less wood cutting would be entailed. I don’t mind doing work to get what I want. I’m not workophobic. I like cutting wood. But I like getting shit done too, and cutting longer wood means more wood cut at the end of the day, which equals more charcoal. I also like efficiency.

So I put agave leaves and charcoal pit together. I could dig a long pit kiln, burn the long wood and use the residual heat to roast long agave leaves to soften them up for processing out the fiber.

Ideally the kiln would have been even longer for even less wood cutting (UPDATE: which I've now done and it was great for long unprocessed limbs with twigs and all), but I didn’t have a ton of wood set aside to fill it this time around, and didn’t need a huge pit to cook the leaves in. I think the opening was probably about 6 feet long and sloped down from there on all four sides. I didn’t screw around trying to make it nice, even though I had already generated ideas about how to best build and run such a pit. This run was all about observing what did happened, rather than second guessing exactly what was going to happen. I knew I’d learn something by just digging a hole and going for it. I lined the bottom of the pit with bricks to retain heat for roasting the agave. It is sometimes possible to use just the heat stored in soil to cook things in the ground, but I knew it wouldn’t be adequate in this case, especially since the ground was already wet. I had doubts that one layer of bricks would even provide enough mass for heat storage, but I just left it at that. I think more mass would have been better, but it worked okay.

The fire was built and maintained until the pit was fairly full. The coals were then raked out (most of them anyway) and a few scrappy sacrificial leaves laid on the bottom against the hot bricks and coals, followed by the remaining leaves. About a gallon of water was thrown on for steam, and the dirt was piled back on as quickly as possible. No really, as quickly as possible, like all out, fast as you can. (No pictures of putting the pit together, since I was rushing in order to retain precious heat.) The charcoal was quenched with water on the ground. A small brush fire was built on top of the pit for about 8 hours to keep heat in.

Here is some of what I learned.

The cone kiln concept works. The principal is so simple that I’m surprised I hadn’t heard of it before and almost surprised that I didn’t think of it myself. You start with a fire and establish a layer of coals covering the bottom. When each layer is almost burned to coals, another layer is added. Each new layer effectively uses up incoming oxygen before it can get to the coals below, thus putting them out, or causing them to barely burn. You can see this effect in a brush burn pile. Generally there is a good pile of unburned charcoal in a burn pile when the flames subside, and it takes up to a day or more to finish burning out. That is with piles that are managed for less smoke by piling stuff on one layer at a time as the fire burns, which is how I usually do it. I don't like making piles way ahead and burning them, because lizards, frogs, salamanders and snakes all move in and get burned up. A brush pile is a wildlife magnet. Kelpie builds brush piles and burns them from the top down to reduce smoke and produce char. The cone pit burns with very little smoke. Low smoke is a huge departure from most primitive charcoal making methods, and one of my criteria for a good system of char production. You could probably do this in many backyards without raising any eyebrows or calls to the fire department.

I think that using wood of similar size for each layer is important. Each new addition should burn down fairly evenly, that is with all pieces burning at a similar rate. If half the wood is one inch diameter and the rest is 3 inch, the one inch material is going to be burned to ash by the time the 3 inch stuff is burned down enough to add a new layer of fuel. This principal probably would also apply to differences in wood species and condition, i.e. oak mixed with pine, or green mixed with seasoned.

The layer of wood added should be tightly spaced and/or thick enough to adequately smother the fire below. Think of each layer of wood as an intercepting shield. the shield should adequately cover and protect the layer below from infiltrating air. I chopped the pieces to fit as necessary, and packed them pretty close together. I left just enough room between pieces to let a little air in between them to keep it all burning cleanly. More experimentation should be revealing as to what can be gotten away with. At some point too much attention to detail is going to cost more than it gains.