"...growers, shippers and retailers, who have been giving us food that looks great but often isn’t for over a century, have their own agendas."

When writing about apples and their propagation in both technical and popular literature, it seems almost compulsory for the author to assure us that if we grow an apple from a seed, that it will not be the same as the apple that we took the seed from. We are usually further assured that the chances of actually growing a toothsome new apple variety bursting with juice and flavor from those little seeds are extremely dismal. One might imagine, and sometimes we are even subject to descriptions of, the small, hard, green, sour, bitter and worm eaten result of such an experiment! In the past, I have been discouraged from making the experiment of growing apples from seed by this common knowledge, especially upon learning that modern apple breeding programs cull thousands of seedlings to find one gem worthy of propagation.

I will concede that under many circumstances growing apples from seed may not be the wisest course of action or the most likely to yield the greatest reward. Who wants to invest in the time and patience required for the growing of an entire tree only to find the secret unlocked from it’s genes by our roll of the dice is some hard green apples for the kids to throw at each other? Not I, not ye, not no one! I only know of one apple that is supposed to grow fairly true to seed and that is the Snow Apple A.K.A. Fameuse. Otherwise the chances are that a seedling will be at least somewhat unlike it’s parents. But then, this genetic variability is what really makes the apple able to give us the great variety that it offers.

The genes of the apple hold many secrets. Combinations and mutations of it’s genes have already yielded a remarkable array of attributes. Resistance can be found to many diseases. Northern Spy is nearly immune to the wooly aphid and breeders used it to bring us resistant rootstocks. Some trees do well in wet soil, some in drier soil. Some require a long chill in winter while others can bask in tropic heat with virtually no chill and not only grow and fruit, but also produce a delicious apple. And we all know that apples come in a great variety of shapes, colors, and sizes. Some will ripen in early summer and others can hang on the tree well into winter and even into the spring. Some must be eaten post haste before they begin to deteriorate while still others have kept in a common cellar for two years. What most do not know however, is the flavor potential locked within the gene pool of the apple.

Apples encompass an amazingly diverse range of flavors which most people never even have a chance to explore. banana, mango, fennel, berry, pineapple, citrus, cherry, rose, vanilla, spices, pear, wine, “apple”, jolly rancher’s candy and more all lurk in those genes. Probably the greatest variety of flavors contained within any fruit. While most post Red Delicious era consumers are obsessed only with the crunch of an apple, it is primarily the world of flavors contained in domestic Apples which drive the obsession of amateur grower/collectors like me and which makes the roll of the dice when growing out apples from seed seem not only worth the risk, but downright compelling!

I am no expert in the matter, but I have come to think that we have a better chance of ending up with something good from that seed than we are often told. Maybe the idea that seedling apples are a one-in-a-gajillion chance is one of those ideas that is repeated by one author after another becoming common knowledge with a life of it’s own... just minus the knowledge part. If the idea interests you, please read on, because previous to the turn of the century the vast majority of apples the world over were grown from random seeds, and we can do better than that.

In the 19th century, Johnny Appleseed (John Chapman) ran around planting apple seeds. Being a folk hero, he gets all the credit, but lots of people planted seedlings and seedling orchards, or collected seeds from fortuitous trees that bore good fruit. As a result, American Apple diversity absolutely exploded over a relatively short period. Most of them, even the named and propagated varieties were just not that great when held up against the best apples out there, old and new, but there is also no doubt that many valuable new varieties came into being from this upswelling of apple culture.

Keep in mind, that Apple breeding is a progressive process in which we build on the foundations laid before, so progress in the field should be continual, and our chances of breeding good apples should increase with each generation. I am all for preserving diversity, but I’m inclined to preserve diversity worth preserving. I’m sure it’s uncool to say this, but I don’t think it is worth our while to catalogue and preserve every single heirloom plant out there, Apple or otherwise. It is at once too daunting and too narrow minded. Gajillions of varieties have already come and gone before us to get us where we are now. we need a certain amount of diversity to work with in breeding up new stuff, but we just don’t need it all, and some varieties are simply not worth the effort. The point is really to move forward in a holistic sort of way.

What I am actually more interested in than mindlessly conserving everything that has gone before is increasing, or at least maintaining diversity. Sadly, the industrial food supply line is antithetical to the idea of diversity. If we leave it up to them, we will lose any apple that is not what apple breeders, growers and marketers think we want and is easiest to get to us. Thus would we lose our lovely russets and our lumpy, bumpy and otherwise unfashionable or uncomely, but delicious, apples. In order to preserve crop diversity in a way that is relevant, we have to live a culture of food in which those plants are important to our lives. Apples can still use improving and diversification, and I think that the layperson and fruit hobbyists can have a place in that process.

Here is an interesting piece of history. At the Geneva agricultural research station in 1898 and 1899 an experiment in the growing of new apples from intentional crosses was made. The experimenters claimed that up until this time, theirs was an altogether novel idea. The selecting of seeds from good apples was commonly practiced, but hand pollinating the flowers to cross two specific apples was, if we are to believe the authors, nearly unheard of. The operators grew what by modern breeding standards was a measly 148 seedlings of intentional cross pollinations using 10 different varieties of apples as the parents. Of those 148 seedlings, 125 survived and at the publication of their report “An Experiment in Apple Breeding” in 1911, just 106 of those seedlings had fruited. After which they proclaimed....

“all will be interested it is certain, in knowing how many of the progeny of these crosses seem to the writers to have sufficient value to name or test further.”

Well yeah! way to work the suspense... drum rollllllllllllllllll- out of the 106 seedlings, 13 varieties were deemed worthy of propagation and naming, those being Clinton, Cortland, Herkimer, Nassau, Onondaga, Otsego, Oswego, Rensselaer, Rockland, Saratoga, Schenectady, Schoharie, Tioga, Westchester, and 14 deemed worthy of further testing, but not worth naming. Wow!, they must have been stoked! At the time apple breeding was in its infancy and few apples had known parents although one parent was often known, claimed or at least suspected. The report, is detailed and I’m sure much was learned from the experiment regarding the breeding of apples... but times have indeed changed.

Most of those first apples selected at Geneva in their probably overly generous enthusiasm are basically unknown today, with cortland having notably stood the test of time. It is encouraging though that the apples they came up with in such a small lot were not just plain bad, but about 1/4 of them considered worth naming or at least considering. From there out, apple breeding became increasingly complex and the goals ever more narrow.

The Geneva station remains a full time apple breeding operation using traditional breeding as well as unnatural marriages of bacteria, insects and fungi with apple genes to create GMO apples. Something I read recently claimed a 1 in 10,000 ratio for seedling selection, meaning that out of 10,000 seedlings only one will be chosen to become a new marketed cultivar. The results of these programs will no doubt be more disease resistant apples that look really “good” on the shelf 6 months after picking. Many of them taste good as well and one can’t really argue with those results. There is a place for these apples (minus the GMO's in my considerable opinion) and these programs, but the selections are skewed by the intentions of the researchers.

Susan Brown, the head of apple breeding at Geneva breeds to make growers money. Like most research anymore, these programs are married to industry. While the products are sometimes great, I don’t see the soul of the apple in these efforts. Some of the most famously flavored apples relished and praised by millions throughout history would never be selected in this paradigm because they don’t look “good” enough or they lack disease resistance. It pains me to think of all the amazingly flavored apples that must be culled from these programs every year because they don’t meet the very long list of criteria that a modern cultivar has to live up to in order to make the grade in a commercial paradigm. There can be no doubt that out of 10,000 seedlings the one that tastes the most amazing and the one that looks the "best" are not going to be the same apple! But growers, shippers and retailers, who have been giving us food that looks great but often isn’t for over a century, have their own agendas. Their criteria are not only flavor, but good looks, storage ability, productivity, and lower labor and chemical inputs. Oh yeah, and Canadians have been laboring away quietly on a genetically engineered apple which doesn’t brown when it’s cut and is on the fast track to store shelves in the U.S. Now that's progress!?

So, my objection to modern apple breeding programs is that, while their results may often be very useful to us, their goals are in line with a culture based around supermarket consumers. What’s wrong with that? All kinds of things. First of all, the supermarket consumer paradigm discourages diversity. Brands are built up as recognizable entities, ideally (but rarely so) with uniform quality. In a way, that has always been the case, but on a local basis. These days shippers and marketers cover large areas, global actually, and global diversity is becoming lower as a result. Another issue is that, cosmetics are a goal that is placed above eating quality. Sure, breeders are making great strides in growing up apples that look good and taste good, but appearance is and always has been more important. Thirdly, another important goal is to make money. Growers have provided us with crappy apples for decades at least, because in the grocery store paradigm they have a dependent and basically captive customer base. I won’t go on, but let’s just say that, in short, the goals of consumers v.s. producers, packers, retailers, and ultimately the breeders that cater to them, are just not the same, and that we can’t predict the many ways in which that might affect us. One way though is that the majority of modern cultivars are bred from one of six cultivars deemed desirable by the industry, leading to a lack of diversity and inbreeding as this article points out.

"The author’s analysis of five hundred commercial varieties developed since 1920, mainly Central European and American types, shows that most are descended from Golden Delicious, Cox's Orange Pippin, Jonathan, McIntosh, Red Delicious or James Grieve. This means they have at least one of these apples in their family tree, as a parent, grandparent or great-grandparent.

Six apples as "ancestors" of the 500 examined varieties

In 274 species (55% of those investigated) the six "ancestor varieties" are represented twice or more in the family tree, in 140 varieties (28%) at least three times, in 87 varieties (17%) at least 4 times and in 55 varieties (11%) 5 times or more."

H.-J. Bannier, Pomologen-Verein,

I’d like to expand for a moment on the cosmetic issue, because I think it is key. I love a beautiful apple as much as the next person, but what is a beautiful apple anyway? In the supermarket consumer paradigm our chances for comparison are limited. A couple of the apples I’ve seen that I would call most beautiful would be passed over without a thought in a modern breeding program because they are covered with a map of cracked russet (russeting, for those who don’t know is a sort of rough skin layer that covers more or less of some apples). There is a class of Apples called russets, which are heavily russeted. While many people might consider them to be less than attractive, I think the vast majority of people in America today have never even tasted one, even though they have been prized in the past as a group for containing varieties of exceptional quality of a specific type. We perceive our world with expectations and standards that are built up from many sources, judging, accepting and rejecting based on those ideas. While the uninitiated may view a rough yellow russet apple with suspicion, I think that the russet eating veteran sees these apples very differently indeed. Besides, heavy russeting is thought by some to contribute to the style of flavor this group of apples possesses.

JUST ASK ALBERT!

One of my heroes is an apple breeder named Albert Etter. Albert is the source of some of the apples I’m using in my breeding efforts. He grew a lot of seedlings but, like the early geneva experiments, he was very encouraged with the results of intentional crosses. So, without further ado, in the interest of supporting my theory that it is worthwhile for amateurs to try growing a few apples from seeds, here is Albert’s experience as reported in the Pacific Rural Press 101 years ago, roughly contemporary with the Geneva breeding experiments.

”Mr. Etter's Work with Apples.

To the Editor: Making good my promise, I am sending you another bunch of my new varieties of apples grown from selected seed. l am not saying much about these varieties yet, because they are too new and untried. Still, it might be as well for those interested to prepare for many new varieties of new and striking characters. I see that the publication of my personal note to you, in your issue of October 7, has aroused an interest in this branch of my plant-breeding work. This work has been under way for many years in a preliminary way, and now all is ready to try out thousands of seedlings. I will not say just how many, because I do not know. But, if facts uncovered as the work progresses justify it, there is ample room and facilities to try out several hundred thousand varieties in the next twenty years. Results obtained so far more than justify my plans for the future, which are to make haste slowly, and sell guaranteed stock under a registered or copyright label."..... “When I had figured out the lines of desirable variation in the dahlia species', as a boy of eighteen, I dreamed of taking up the apple trail. The best horticulturist I knew in that day, an old gray-bearded man, After listening to my dream frankly told me to forget it. The idea of trying to do that which trained men, with all the recorded knowledge of the world on the subject, could not do, or they would have done it long ago! But I could not forget it. As I remember, I kept thinking of it until I reached the conclusion that the apple varieties we have at this late day are a harum-scarum lot, to make the most of it, to represent possibly 4000 years of human endeavor. What Is more and worse, as apple breeders, we are making little progress.” [Mr. Etter's seedlings which we have examined with much interest and have kept on exhibition in our office since their arrival, certainly justify much more than he claims to have attained in his sketch of his preparatory work. They have very striking and novel characters, external and internal. In our judgment he has already attained things which generations of apple-growing have not developed. We are glad to put on record this early record of his work which will some day be looked upon as of great historic interest. — IMs.]

Apple Breeding. —A few seedling apples have already been fruited and there are also 1000 seedling grafts approaching fruiting age on the place and 1000 ungrafted seedlings, which it will take longer to try out. In this connection, Mr. Etter states in a recent letter: "My new apples are looking better every day. One is a Wagener that looks a great deal better than the Wagener and is better flavored, too. The other is a seedling of the Rome Beauty, and is a beauty beside its parent now, and as near as I can judge at this date is going to be considerably better flavored, too. "This apple breeding proposition now looks as though I am on the right idea, and, if such is the case, I will be able to do what I prophesied I was going to do over 20 years ago—produce more and better varieties of apples than the world possesses today. That is a big task, but if I am right, it will be comparatively easy. If I were not right, how could I get seedlings of the Wagener that outclass its parent the first time?" Such success with only a few seedlings indicates that better success will follow work on a more extensive scale, especially as the experience obtained will furnish a guide to future operations. Just here a few words on the origin of apple varieties is not unfitting. Without doubt practically all of our old standard commercial varieties, like the Bellefleur, Spitzenberg and Newtown Pippin, are the result of chance, not design. Seedlings came up by chance, fruited and their merit was recognized. Crossing of varieties for seedlings of merit was hardly done, if at all, and if done was not based on scientific principles. The seedlings of great merit have been carefully preserved and propagated, but the unknown possibilities of new varieties have not been explored. Then also, the joy of discovery of new varieties evidently warped the judgment of many discoverers, and an astounding proportion of the 500 named varieties grown are of as little merit as apples well could be. In fact the average of the seedlings grown purposely on the Ettersburg ranch is fully equal to the average of the 500, and the best of the seedlings is in the class with the best of the 500. In other words, the new apple breeding is being conducted along careful and systematic lines as compared with the raising of seedlings by chance and then finding which of the seedlings were good by chance also. Of the two methods, theory and results, both indicate that the systematic and scientific one is sure to produce in a short time varieties surpassing those obtained in a haphazard way through many generations.”

Note here several things about Etter’s experiments and comments.

One is that he thought most named varieties were not that great. My experiments here in growing out and fruiting many varieties confirm this idea. Apples could stand to be improved.

Secondly, the crossing of apples intentionally using quality parents is much more likely to yield good results. The explosion of variety in American apples was due to the growing and finding of random seedlings, and that worked tolerably well. We have a world population of 7 billion now. If .00001 percent of those grew a dozen apple seeds from selected parents, that would be 840,000 seedlings to pick some great apple varieties from! Exactly what the scientific lines Etter refers to I don't know, but I'm inclined to think that most of his success was due to his strong vision, a willingness to take chances, and taking the effort to collect and compare over 500 varieties before choosing the parents he would work with.

Thirdly, some old learned guy told him not to bother, but he did it anyway!

Albert came up with some excellent apples that are finally attracting the interest of small scale growers and collectors. The Wickson apple in particular is going viral in the last few years, and deservedly so.

Having an interest in apple breeding on a small home scale, I have always marveled at the numbers you hear regarding seedling to cultivar ratio like the 1 in 10,000 mentioned above. I'm undaunted though, because when you read older stuff like the Geneva report and Albert Etter’s reports, it is clear that they were not dealing in the thousands to one ratio to produce a fruit very suitable for eating, and they were not uncommonly an improvement on what was already available. That of course was a different time and goals were different, but those goals were more in line with those of homesteaders and foodies of today than most modern breeding efforts. We already know that increasing commercialization of the industry along with the requisite shift to home economies based on consumerism killed apple diversity which apple-collectors and enthusiasts around the world are now scrambling to save from extinction. In reading research material on apples from the 19th century, the trend toward commercialization to supply a society moving further and further from the farm is very apparent. Discussions among growers increasingly placed productivity, looks and keeping abilities above eating quality. The modern programs can help with that problem and they have by providing apples which will keep well and look good while flavors are steadily improving. However, taken as a whole, from the breeder to the farmer to the table the industrial food system is a fundamentally flawed one which never has, and never will have, the best interest of consumers and communities in the forefront. That's not so bad, if we don't neglect our responsibility to maintain diversity, and one way we can do that is to breed new apples building on the work of modern breeders, as well as by using heirloom varieties with special qualities.

And in the meantime, we would do well not to let our apple diversity pass into oblivion. Stephen Hayes, who is AWESOME, makes the argument that we should not spend our time trying to grow new apples from seed when there are so many heirlooms to be saved from extinction. But I respectfully disagree. I think all homesteader types who grow fruit trees should be growing heirlooms, but there is room for experimentation for the geekier among us, and I think we can have our apples and breed them too! a few apples grown from seed can be grafted onto existing apple trees to bear with very little time investment or, for the more committed, a small growing plot can be kept to grow the new apples out on dwarfing rootstock.

I guess to sum it up, apples could still use improvement, but if we leave apples to the hands of the big outfits with lots of resources they will continue to produce results that cater to the source of those resources. It is up to no one, except everyone, to preserve apple diversity and move the creation of new and exciting apples forward. Small scale breeding efforts such as anyone with a tree or two can do in their back yards, are where that battle can be fought. However, we should not let the apple industry set the standard, because their goals are different. I guess what I'm saying is that if we don't pursue unmarketable lines of apple improvement, apples will only develop along certain restricted lines.

I would encourage you not to think just in terms of your accomplishments, or lack of in a backyard breeding endeavor, but rather view your efforts as a part of a larger effort. Any of us may or may not breed apples that are really amazing and worthy of widespread fame and replication. However, taken together as a whole, we most certainly will!

Two springs ago, I spent maybe two or three hours hand pollinating flowers and produced a couple hundred seeds. Of those, over 100 sprouted in the greenhouse and were grown out in a small nursery bed. Last spring I pollinated a few more, and have further plans this spring. This month, the one year old seedlings were grafted onto dwarfing root stocks and planted in a nursery row. Next year they go into a trial plot planted close together, and in 4 or more years I may have some results to report. The total time devoted to this project has not been very great. In the next installment, I’ll show you how easy it is to pollinate a few apples and grow the seeds out. I have hopes that I can help nudge over the cliff others equally seduced by the chance to taste brand new apples that have never existed before. Pollinating a few flowers is the first step. Yes.... jump.... just do it.

Further reading on Albert Etter and his apples:

Albert Etter's red fleshed apples article by Ram Fishman foremost expert on Etter and his apples.

Informative Greenmantle Nursery page on Albert Etter's apples

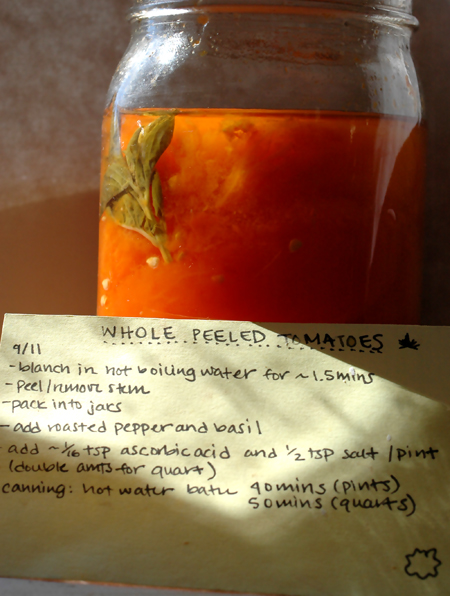

Tomato season is finally on here at 1800 feet in coastal Northern California. Having just mentioned canning tomatoes in the Mega Canner post, as well as also having recently been enjoying my few remaining jars of them, it occurred to me that my method of canning tomatoes might be of some use to other people. Over the years, I gradually devolved toward a very simple tomato canning system that is not too much work and leaves me with a very versatile product.

Tomato season is finally on here at 1800 feet in coastal Northern California. Having just mentioned canning tomatoes in the Mega Canner post, as well as also having recently been enjoying my few remaining jars of them, it occurred to me that my method of canning tomatoes might be of some use to other people. Over the years, I gradually devolved toward a very simple tomato canning system that is not too much work and leaves me with a very versatile product.