In this video I address some common terms used in describing lumber and lumber milling. More importantly, some ideas about language regarding it’s misuse and limitations. I’ll talk about grain orientation in this blog post, but the language stuff will mostly have to wait for another post sometime. It’s a pretty big topic to bite into and I’d rather wait until I have the time and mindset to articulate my views as well as possible. This video was totally off the cuff and I was actually on pain meds after my recent appendix surgery, so it could have been better, but it is what it is. I think the language portion of the video is extremely important and the ideas presented are foundational for me in my world view and how I think.

LET’S TALK ABOUT END GRAIN ORIENTATION

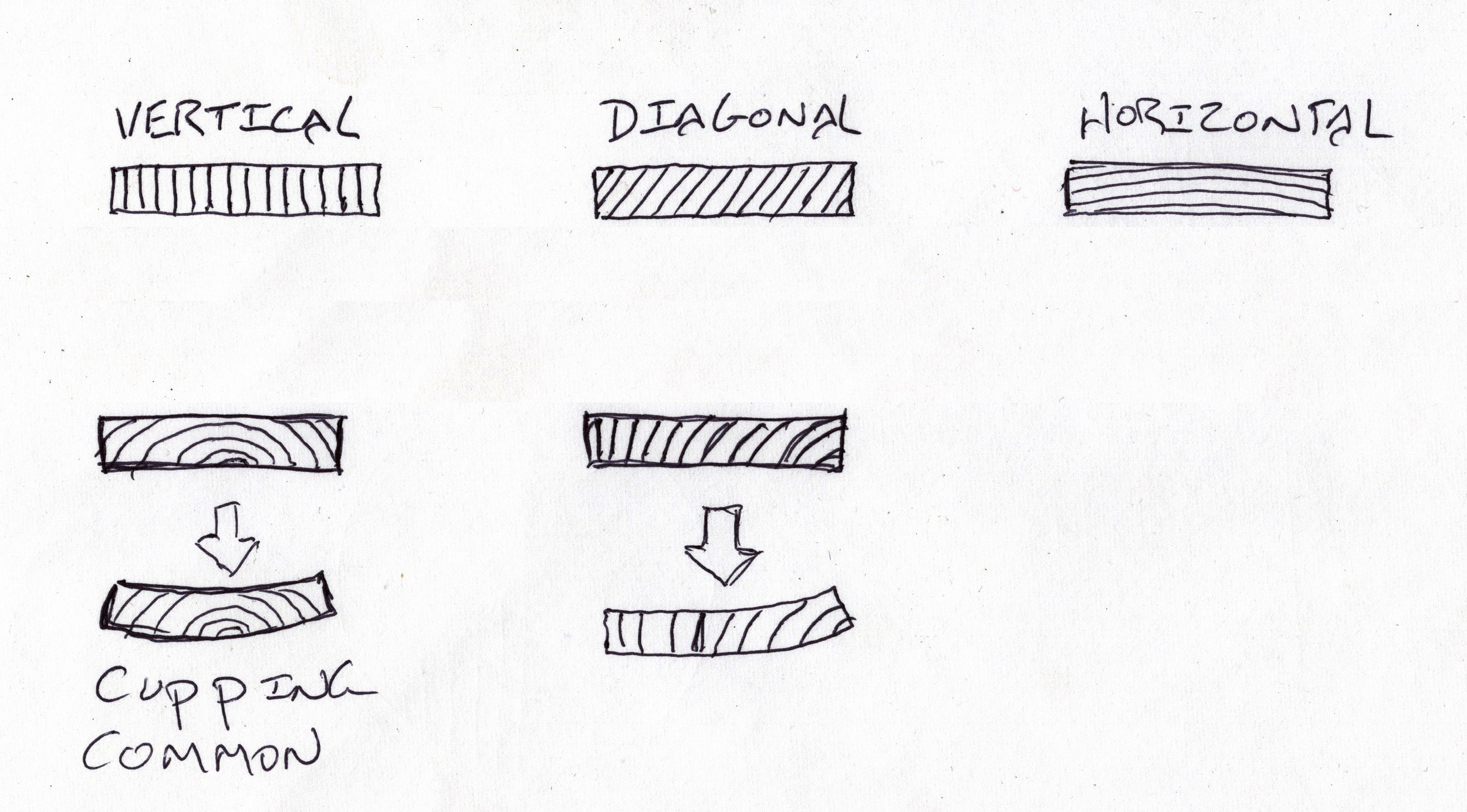

You can take a tree that has relatively homogenous properties as a wood, and cut two boards out of it that have very different appearances and properties. The difference has to do with growth ring orientation. We might describe the basic growth ring orientations in lumber as vertical, diagonal and horizontal. and obviously there are a lot of variations between them. See the diagrams below. Vertical grain is considered very desirable in many cases, but diagonal is preferred by some in some cases and even horizontal if a certain grain pattern is desirable. But in terms of stability, wood with about a 45º to 90º orientation is much more stable and less prone to cracking and cupping in seasoning or over time. The closer you get to horizontal, the less stable the lumber typically is.

Showing common end grain orientations and characters. vertical is the most stable orientation, and gives large, long flecks in woods such as Oak and Black Locust, which have prominent medullary rays. Diagonal grain is great and usually quite stable. The further diagonal grain gets toward horizontal the less stable and well behaved it is. Unless some specific look is wanted, horizontal grain lumber is not generally preferred, and even less so if it is from a small diameter log and the rings are very curved as on the bottom left. Of course there are many variations between these basic common examples.

Go look at an old wooden board fence. Typically you will see a clear pattern where any boards with horizontal grain are more cracked and more cupped than boards with diagonal or vertical grain. Boards that have diagonal grain but tending toward horizontal will have increasing problems. Boards with horizontal or close to horizontal grain will also have more tendency to not just crack, but to delaminate in layers along the growth rings. A fence is sort of a worst case scenario, because the boards are left exposed to repeated wetting and drying and hot drying sun. The wood shrinks and expands and if a board is going to show it’s hidden stresses and weaknesses, it will do so if nailed to a fence for years. If I were at a lumber yard buying fence boards, I would try to pick as many boards as possible with a grain orientation of vertical to 45º, with no knots or grain irregularities. Assuming the wood is a species suited to fence boards, that fence would last a long time, where my neighbors fence with randomly selected boards ranging from horizontal to vertical would have more cupped and cracked boards over the same span of time.

Grain orientation also affects the look of the wood quite a lot, especially in woods that contain pronounced medullary rays. Medullary rays are corky, dark structures in the wood that radiate out from the center of the tree. They can be very pretty if oriented certain ways in the board.

This triangular billet shows the 3 main grain patterns in Tan Oak by end grain orientation in the board. Note the long flecking of the medullary rays in vertical grain wood. If you look at the end grain of the vertical orientation, you’ll see the dark medullary rays as lines running horizontally. They run from the center of the tree outward, like spokes and show on the face of diagonal boards as this flecking effect. These get shorter and eventually less interesting the more the grain tends toward diagonal. Vertical grain is also typically the most stable orientation. The only milling method that produces this orientation in 100% boards is what I call Rift sawing.

The diagonal has a nice grain pattern, but not the high level of interest invoked by the flecking in vertically oriented. It does look the same on all sides though and anything from 45º to 90º, and even somewhat less, is usually stable, quality wood.

Look how badly the horizontal face has cracked. There are possibly a few small cracks on the diagonal face and none at all on the vertical face. This illustrates how horizontal milled wood is typically more prone to cracking and also cupping and shrinkage. In many woods, you’ll see the growth rings show as a distinctive and familiar pattern on the face of horizontal grain boards, but tan oak doesn’t really show that pattern when cut this way.

If the tree is cut with perfectly vertical grain, as shown, the flecks of color which are the exposed rays will be of maximum length across the face of the board. On the edge of the board there will be no flecking at all.

Boards with horizontal grain will have no flecking on the face, but flecking will be present on the edges.

Lumber is often described as to the way it was sawn. The sawyers who cut out the boards use methods suited to the species, the mill and blade type, efficiency, log size or qualities and quality of finished lumber. Often the easiest methods don’t yield the most quality lumber, but may be perfectly functional and adequate, such as for rough building material, or the method may be economically efficient regardless of lumber quality. Look through the diagrams and the descriptions below, which describe different methods. Lets look now at common methods and terms for sawing logs into lumber.

SAWING METHODS

There are a lot of different and creative ways that boards are cut out of logs. For instance, although horizontal grain wood is generally more problematic from a practical perspective, there are methods that actually maximize boards with that grain orientation. The below however are some common ones that are relevant to this conversation.

PLAIN SAWING (aka, live, through or flat): It is typically easier for a sawyer to just run the log through a blade over and over with out resetting the log’s position. It is quick and easy. But it produces boards with every kind of grain, from vertical to flat, some very poor, some very good and some in between.

QUARTER SAWING: Diagrams available on the net show two common quarter sawing techniques. In both strategies, the log is first quartered, then it is sawn in such a way that it produces just wood with vertical and diagonal grain, around 90º to 45º. Quarter sawing does not make the most wide boards possible, but it creates 100% high quality grain orientation. To do so, it requires much more time and effort, so it is usually reserved for higher quality wood or to create lumber for certain uses or grain appearance.

RIFT SAWING: The method most commonly termed rift sawing is even more hassle. It makes a lot of cuts in a way that makes no sense from the perspective of efficient lumber production, and actually wastes a few boards worth of wood! All in the name of getting as many perfectly 90º grain oriented boards out of the log as possible. But, clearly in some cases people are willing to accept those disadvantages to get all vertical grain or no sane person would do it.

SAWYER V.S. WOODWORKER NOMENCLATURE

The Sawyer has had his way with the log, and we already looked at how grain orientation affects the lumber appearance and stability, now on to language and the consumer. It is common to refer to boards by the supposed method used in sawing them, such as quarter sawn, rift sawn, or plain/flat sawn. In a recent video, I invoked the term rift sawn, and was told by a commenter that I used the term incorrectly, and that rift sawn lumber is actually lumber that has about a 45º degree grain orientation. (that comment thread is in the bottom of this post) The truth is that in lumber and milling terminology, there is no authority, and no consensus. As such, there is no correct or proper term. Here is a Duck Duck Go search that illustrates the diversity and confusion of terms.

duckduckgo.com/?q=rift+sawn&t=ffab&iar=images&iax=images&ia=images&iai=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.protoolreviews.com%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2Fptr%2F3000.gif

There is also a strange divide between sawyers and the the lumber merchants and users which reveals a hard contradiction. If one wanted to do the work, a stint of historical research might yield an evolution of these terms that could create a basis for claiming that certain terms are more justifiably used for certain methods of sawing. To get woodworkers and lumber merchants to start using a “corrected” terminology seems like herding cats. Sure it would be of utility to adopt a common convention and that would avoid much confusion, but between the unlikelihood of effectiveness and the level of effort involved, it doesn’t seem important enough to bother. Regardless, I’ll make my argument for what a less confusing common convention might look like at the end of this article.

A board is what it is and is not the terms we might use to describe it. Even if 100% of people agree that a board is correctly and accurately described by the term quarter sawn, or rift sawn, it is still not either. The object, the board just is what it is. Unequivocal acceptance of terminology implies that there is somehow, somewhere a consensus, or authority, or that there is some absolute grounds for using a given terminology. I do not believe that any of those are true. If anything, I think we are confusing ourselves by referring to lumber by the method of sawing, because it is impossible to know what method the sawyer used in all cases. I often use these sawyer terms myself to describe lumber, but it really doesn’t make sense.

It is my best guess that the lumber terminology that refers to a board as sawn in a certain way, derives from sawyer terminology referring to the strategy used to cut up logs. For instance in quarter sawing, the log must first be quartered in order to pursue that strategy. But there are also two and quite different methods of sawing up those quarters, which are both commonly called quarter sawing, and more variations on one of them.

I think it is likely that the term and method which seems to be most commonly referred to as rift sawing (as a strategy, not as a grain orientation!) derives from riven lumber, which is split from logs rather than sawn. If you split a log into halves, then quarters, then 1/8ths, then 16ths etc, then hew those down into boards with an axe, you get about the same thing you get with what seems to be most commonly referred to as rift sawing; the end result being that all grain will be vertical. Some entomological and historical research might help support or call into doubt that theory, but I can’t be bothered. I just don’t think it matters that much. The only reason I’m talking about it so much is that I think it offers a window into our use of language and our attitude about words and definition, and the validity of convention and authority.

Grain orientation and sawing methods is an interesting study of language, because it involves two main parties, the lumberman and the wood consumer. The lumberman may sell the lumber merchant wood that is literally quarter sawn, which involves first cutting the log into quarters, thus the term. But in selling wood to consumers, all that really matters is the grain orientation, not the sawing method. The truth is you can get 90 degree grain boards out of a single log when sawn by any of the above illustrated three most common methods, and others; it’s just that you will get more or less of it. This creates a perfect storm for confusion. It makes a lot more sense to dispense with sawing terminology on the merchant/consumer end, and use grain orientation to describe lumber. It would make sense to use sawyer terminology if you were buying a whole log, or having a log custom milled, otherwise, it doesn’t matter how the log was sawn, just the end result.

The culture of wood consumers and lumber merchants it seems has somehow come to often use the term rift sawn to indicate lumber with a diagonal grain. But the most common use of the term rift sawing from the sawyers end is a method which produces zero diagonal grain boards! It’s sole purpose is to produce 100% vertical grain boards at any cost.

The term quarter sawn on the other hand commonly seems to indicate vertical grain wood in the lumber world, while the methods most commonly called quartersawn in milling produce both vertical and diagonal grain. So, if the terminology originally derives from sawyers and the mill, it could be argued that the lumber merchants and woodworkers have it sort of backward if anything. But are they wrong?

Language is not just manufactured, it’s a product of living, changing culture. I once read a thread where someone posted a picture of what almost anyone would call a hatchet and some guy said, that is not a hatchet, a hatchet is …. I don’t even remember what he said, some old type of chopping hatchet axe thing that was different. But if you walk up to 100 people on the street and say what is this and hand them a standard short camp hatchet, they are almost all going to call it a hatchet, with maybe a random person calling it a camp axe. So, basically it is now effectively known as a hatchet by majority use. Language is fluid and evolves over time. Which came first, the dictionary or the word? The dictionary attempts to maintain standards and conventions, but it is also there to document and legitimize new and changing language. And regardless of all of that, a board of whatever configuration just is what it is in spite of our monkey chatter.

The nomenclature around lumber and milling is very confused and confusing. Because of the contradictions in milling and lumber terminology, and because ALL of the most common milling methods produce vertical grain lumber and all but one produce diagonal grain, I think the best argument that can be made toward a more sensical standardization of grain orientation terminology, is to leave the sawyers terminology to those milling the wood. If woodworkers and lumber merchants were to stick to grain orientation and work toward a convention around that, much confusion could be avoided. Not only is it not possible to take a vertical or diagonal board and know what method was used to cut it, but it is also completely irrelevant to the user. The obvious exception would be if you are having a log custom milled. But, you’d better make sure that you and the sawyer are on the same page regarding terminology of sawing strategies.