I compiled a bunch of references while researching Potato Onions which are posted below. It is also available as a The Historic Potato Onion- A compilation of early references, which also has links. First though, I have some notes on my impressions and observations on reading through these references. Note that there are many different planting dates and methods of cultivation. That is to be expected, I suppose, given the widely varying geographies that the authors are referring to. See also my previous detailed blog post on Potato Onions, for more details about the onions and their culture, which is probably a better place to start your Potato Onion adventure if you are new to them.

Apparently planting smaller Onions makes fewer, but larger Onions than if larger Onions are planted. I believe what is usually being referred to here is as follows. The Potato Onion has a number of “eyes” growing inside of each Onion. I believe each of these “eyes” probably forms a new bulb each of which also has more “eyes”. The larger Onions have more eyes and therefore produce more bulbs when planted although of smaller size due to competition within the plant itself. The smaller Onions having fewer eyes produce fewer Onions but larger ones due to decreased competition for soil resources. There are also however references which say that one small Onion will grow into just one large Onion. I don’t think I have ever seen this happen with the yellow potato Onion variety that I have, so I suspect that it is either incorrect or that there is a variety which does behave this way. It is also possible that I just have not planted small enough sets to observe the one-small-into-one-large phenomenon or, further, that I have observed it and simply forgot. I will be observing the results of growing different sizes of bulbs more closely this year. The idea, as some authors mention, is to grow the right proportion of large and small bulbs to assure larger ones for eating while yet retaining enough small bulbs for good seed. Potato Onions often have internal division where the walls of skin between the “cloves” or main “eyes” have dried off. Some mention is made of dividing them along these lines for planting. I have done so, but not in a very observant manner.

Another interesting recommendation is to plant small Onions on rich ground to grow a crop of large eating Onions while growing a crop of small seed Onions by planting large sets into poor ground. No doubt the size of the seed Onions could be reduced further by crowing as is done is Ghetto rows for growing the common small onion sets that many people buy for growing bulbing Onions.

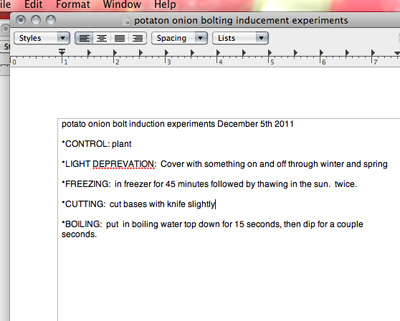

Some authors point out that the potato Onion rarely if ever goes to seed. I have seen mine go to seed and Kelly Winterton is raising new varieties from seed he has saved from Yellow Potato Onions. It seems that the white variety with smaller bulbs is more likely to go to seed, but it seems less desirable than that Yellow Potato Onion. I also feel that the characteristic of hesitancy to produce seed stalks is a great advantage of the Potato Onion and that new varieties are best selected with the goal of its retention. I feel that there must be ways to induce the Potato Onion to seed when we want variable genetic offspring for breeding purposes If so, such a technique would obviate the need for Potato Onions which produce seed. Kelly’s Onions are quite large, larger than typical Yellow Potato Onions by manyfold, indicating that we should be developing new varieties from seed.

Recommendations for planting Potato Onions run from September through March. with several references referring to planting on the shortest day of the year. Here in my mild climate I have planted in the fall and left the bulbs unprotected through the winter with, as far as I can remember, fine results (though this may be what I did the one year that they ran to seed). I have also planted in late spring and gotten fine enough crops. In colder climates it is recommended to hill the Onions up or plant them deep in a ridge. When they begin to grow the soil is raked down or pulled away to insure that the forming bulbs have light and air. I believe that the authors who recommend that the bulbs be only touching the soil at the base when the Onions in the cluster are forming are advocating the best approach. The Onions are sometimes inclined to rot if from the bottom while still growing or while hardening off. So, I would say that this operation of hoeing away the soil from the bulbs is essential if the bulbs are planted deeply.

Another concern when planting early V.S. late is how long the bulbs will keep. Bulbs of all kinds will only keep so long in storage. I have long followed the strategy of planting them later so that the main crop comes in late and I can keep it over winter well. If I matured them in July how long would they keep? I see from the references that it was more profitable to plant them early to take care of an early market when larger bulbed Onions were not yet ready. That seems to have been a main niche of the Potato Onion and that may be what kept it alive. Its diminutive size was probably a disadvantage in selling, but was made up for by its earliness. I can see the advantage of this strategy and plan to employ it for market gardening and earlier Onions, but I can attest to the advantage of putting out sets later to secure later ripening Onions for storage. The two are not mutually exclusive and if both are followed with some of the early crop used as one does a green Scallion they could fill a lot of the season with Onions, actually year round.

I found the recommendation to harvest some bulbs in the cluster very young for Green Onions interesting. The author claims that the other Onions in the cluster will be the better for it, presumably growing larger as a result of the decreased competition for resources. It appears that they were sometimes grown just for the purpose of marketing early green Onions as well. The white variety appears to grow smaller Onions, but many bulbs and perhaps it is more suited to this purpose??? or rather not as well suited to being a storage/peeling Onion. Another interesting recommendation on these lines is to harvest most of the Onions in the cluster for Green Onions leaving a few to produce more green Onions the following year. This seems an interesting strategy, but I can’t imagine the bulbs simply being left in the ground. I think that the ripened bulbs would be better lifted and stored until planting time. The bulbs when ripe are just sitting on the ground surface. All of the roots rot away leaving the bulb free to roll around or whatever. Still, as a strategy for growing large seed to continue producing Green Onions for market, it sounds intriguing and maybe there is a way that they could simply be left in, or even on, the ground.

Many references refer to the Potato Onion as a poor keeper. That has never been my observation and private correspondence with others has confirmed that it seems to be quite the opposite. I have stored them with no particular care into the summer from a later ripening crop. Last year I planted some from the previous year so late that they were unable to mature and have stood the winter with green leaves. I have also tried to grow a very early crop and then plant out some of the Onions for a second crop the same year, but they would not grow. I’m not convinced that this two crops in one year strategy is impossible to implement, but the Onions may need to be tricked into thinking that growing before being stored a while is just the thing to do. Perhaps the difference in keeping is early crop V.S. later crop, or maybe it is due to the growing of different varieties than the one I have. I do lose a percentage to rot in storage, but I don’t imagine that it is even 5% in the extreme though the percentage increases the longer they are kept.

It is apparent from some of the references that there are some real fans of Potato Onions in terms of its reliability and ease of culture. Several mention resistance to root maggots, a problem which I don’t seem to have here, but then I grow mostly Potato Onions.

There is some mention of a new and superior White Potato Onion. It seems doubtful that this is the White Potato Onion that survives now because it is of a smaller bulb size than the Yellow Potato Onion. Still, it is possible that it was just misrepresented. Most mention is made of the Yellow Potato Onion. While now there seem to be some red ones being sold (I have not acquired any of them) I see no mention of red or purple Potato Onions in these accounts.

I found the account of a Russian vegetable culture very interesting. It refers to the potato onion as something of a staple. It also says that cutting the leaves was said to make the bulbs larger. It seems unlikely that the bulbs would be larger if the greens were cut much. The author says that they are cut like chives, but maybe the bulbs are actually thinned out leaving more space and soil resources for the remaining bulbs to grow larger as is mentioned in another reference.

Taken altogether, it seems that the potato onion could be a very versatile crop serving as early garden produce, summer peeling onions and late storage onions simply by varying harvest times and stages and varying planting times. Add to these things manipulations using cold frames and the like and we see a great potential. The potential is further potentiated by the fact that the onions do not bolt like the often finicky bulb forming seed grown onions.

______________________________________

______________________________________

______________________________________

This is research material that I compiled on potato onions by searching google books. I thought I would share it to save other interested parties the trouble of repeating the effort. There is a wealth of practical information here. No doubt a repeat search will turn up much additional information in the future as more old books are added to the digital archives. I had to remove the links because they were not behaving in this blog post version, but you can always find the book online by searching a few lines of the text. The PDF version, Potato Onion Research January 2012 should hopefully have intact links.

Steven Edholm, January 2012

http://turkeysong.wordpress.com

http://www.paleotechnics.com

googlebooks search for “potato onions”:

_________________________________

The kitchen garden; or, The culture in the open ground of roots, vegetables, herbs, and fruits, by Eugene Sebastian Delamer, 1855

The Potato-Onion differs essentially from the above mentioned varieties, and might almost claim to be considered a separate species. It is of high antiquity, being supposed to be the kind that was worshipped, or held in reverence, by the ancient Egyptians. Not only does it come to maturity earlier than the rest, but it is remarkable for the peculiarity of never producing flowers or seed. So unexceptional is this habit of its growth, that few gardeners, if any, can say they have ever seen a potato-onion in flower. If they think they have, without closely examining the case, they were probably deceived by some stray shallot, that accidentally got mingled with the crop. This variety is therefore propagated only by the root. Very small bulbs increase to large ones; large ones subdivide into a cluster of bulbs of various sizes.

An excellent, and easily remembered garden rule, is, to plant potato-onions on the shortest day in the year, and to take them up on the longest. This early maturity is taken advantage of by the stewards and cooks of vessels that are outward-bound for long voyages, when sailing at the end of June, or the beginning of July. By this means they are well provided with a stock of an almost necessary vegetable. With potato-onions, followed by autumn sown varieties, and those by good keeping spring-sown sorts, a sufficient successional supply of onions may be kept up nearly the whole year round. And, not only is the potato-onion supplemental to the common sorts, in point of time, but also in constitutional resistance to adverse seasons: that is, when other onions,—especially those sown in spring,—fail, either from ungenial weather, the attacks of insects, or defective seed, the potato-onion will produce a heavy crop. On the other hand, it sometimes happens, though much more rarely, that the potato onions do not turn out well in seasons when Spanish, Globe, Blood-red, and even Tripoli onions, are both abundant and of good quality.

For potato-onions, give the land a liberal dressing of well-rotted manure during the third week in December; dig it in, preparing the ground well, breaking all the clods, and picking out carefully all the roots of perennial weeds. As near as possible to St. Thomas’s Day (on that day, if you can), after having raked the ground, prepare to plant the bulbs by marking out beds four feet in width, with a foot-wide alley between each bed. Fix your line along the bed, six inches within its outer edge, and along this line set your onions, nine inches apart, on the ground, gently pressing them into the soft earth, just deep enough to keep them upright. Set another row parallel to, and a foot apart from, the former; and then a couple more rows, which will complete the bed. You will thus have four rows, a foot apart from each other, and six inches from the outside edge of the bed. The plants might be, and frequently are, planted at smaller intervals, both from row to row and along the rows; but nothing is gained by crowding the plants or stinting them for room. It may be laid down as a general rule, that all young gardeners plant too thickly. One of the last horticultural maxims learned is, that fine and well-grown specimens are obtained in proportion as they are allowed light, air, and an extended area of ground to feed on.

When the bulbs are thus placed in their position on the bed, it will be easy for the gardener, by walking up the side alleys, to draw the earth to the rows of onions from each side, till their crowns are fairly covered. In that state they will be left to stand the winter. If frost has already set in on St. Thomas’s Day, plant your potato-onions as soon afterwards as the weather will allow, remembering always, that the sooner the better. It is a common fault to plant onions too deep; observe, therefore, that the bulb ought not to have more than half its depth below the level of the ground. Supposing it a terrestrial globe, the soil should just come up to its equator. In spring, when the bulbs are firmly rooted, and the leaves from the crown have shot three or four inches, with a hoe take advantage of a dry sunshiny day (that weeds may wither), to draw back the earth which was heaped up against the roots, reducing the soil to its original level, and leaving the bulbs half exposed to the air. Nothing more than occasional hoeings and weedings will be required. If grubs and maggots are apprehended, watering with lime-water will be a useful precaution; but if they have once eaten their way into the bulb, scarcely anything will touch them.

At the end of the first fortnight in June, symptoms of ripeness will be visible, in the flagging and withering of the leaves. When the original bulb has divided into a large cluster, the central knot will be ripe several days before those next the ground. It may be removed by simply lifting it out, which will expose those which remain to a greater share of sunshine. Potato-onions, like the seeding sorts, should be well weathered before storing, which,will be sufficiently effected, when they are dry, by hanging them in bunches in any dry airy shed, or even in the open air, under the projecting eaves of a cottage. Monsieur Mauduit, of Quimperle, who has long been a successful grower of this variety, advises, as a mode of preserving them, to cut off the stem about an inch and a half above the neck of the onion, to split the end which remains into four pieces, quite down, but without wounding the bulb itself, and to leave it to dry in this state. It will be seen that directions to earth-up potato-onions during their growth are directly the reverse of what ought to be done. The potato-onion is well flavoured, and is applicable to all the culinary uses for which onions in general are employed.

____________________________________________________________________

The American Farmer

By John Turner

September 1866

Potato onions may be set until the 20th of the month. Four to six inches, In rows 18 inches apart, is the proper distance.

Potato onions from small ones, can be grown the quickest of any good variety, and are of excellent quality. The small ones cost from $3.00 to $5.00 per bushel, and should be set 8 inches by 15, and barely covered.

____________________________________________________________________

The Farmer's magazine Rogerson and Tuxford, 1844

POTATO ONIONS.

Sir,—I should be glad if any of your correspondents would inform me (through the medium of your excellent journal) what is the cause of the failure in potato onions. In the past year I had a most excellent crop, and they appeared to be well saved; but now, I am sorry to say, they are all rotten. I should be glad to know what dressing is best, whether the same seed should be sown in the same ground year after year, and what time of the year is best to till them. T. C.

St. Clement, near Truro.

Oct. 8th, 1844.

Sir,—I expected that some of our horticultural friends, who are better qualified for the task, would have replied to the queries of your correspondent " T. C." respecting potato onions (Mart Lane Express, Oct. 14). I beg to inform him I had this summer a very good crop, from seed that has not been changed for twenty years. I always plant them in ground manured for the previous crop, as early in the season as it can be got into tolerable working order (they may be set from the shortest day to the end of March), but never two years in succession on the same land. The complaint of their rotting has been general for several years; many persons have discontinued their cultivation on that account; I however, find, by frequently looking over those that are strung, and removing all tainted ones as they infect those touching them, I obtain abundance for the use of my family : the small ones keep best. I have tried, as a substitute, the Strasbourg onion, sown in August, as recommended in a Scotch gardening work, by Walter Nicol, but have not succeeded, as, if sown near the tine he directs, they run to seed in the spring; if later they are injured by frost in winter. I am surprised that no mention of the potato onion is made in the above work, and some others on gardening I possess, as, from their early maturity, when seed onions are scarcely bulbing, there is a very great demand in towns for them.

____________________________________________________________________

Bulletin / Virginia Agricultural Experiment Station, Issues 1-59 1889

As matter of general information, it may be well to mention that all the cultivated onions which form bulbs, belong to the same botanical species, Allium cepa, and that the varieties known as set onions, and the potato onions, have been developed from this species. For commercial growing, the black seed onions have much greater importance than these other forms.

____________________________________________________________________

Bulletin, Issues 15-36: By West Virginia. Dept. of Agriculture 1916

Bunch Onions. For early green onions, onion sets or potato onions should be planted in September or October, in drills twelve to eighteen inches apart in the row. The bulbs, if planted four to six inches deep will require little or no protection during the winter. Sets may be planted in the spring as soon as the ground is in shape, but will not produce as early onions as those planted in the fall, set out two to four inches apart, in rows twelve to eighteen inches apart. Particular attention is called to the adaptability of potato onions to most West Virginia soils and the advantage to be gained in securing early bunch onions.

____________________________________________________________________

Onions for profit:An exposé of modern methods in onion growing (Google eBook) W. A. Burpee, 1893

Potato Onions {Multipliers).—These produce neither seed nor top-sets, but increase by division of the original bulb. They are early, and valuable for market, especially in more southern localities, but do not keep well. Their color is brownish-yellow. According to reports, a pure white variety of superior merit has recently been introduced.

____________________________________________________________________

The profitable culture of vegetables: for market gardeners, small holders ...

By Thomas Smith Longmans, Green and co., 1911

Potato Onions.—This Onion, although not much grown now, is mild and sweet, and gives a good crop with a minimum of trouble. It should be planted, just below the surface, early in January, in rich deeply-worked soil, and is ready to take up about the beginning of July; indeed, old cottage gardeners who favour this variety plant on the longest and take up on the shortest day. If the bulbs are kept out of the ground much longer than the end of January they begin to go soft and useless. When very small bulbs are planted they grow into large ones, but large bulbs multiply into numerous others. Plant in rows 12in. apart, 9in. between the setts. As severe frosts will sometimes destroy the bulbs, it is wise to scatter litter along the rows after planting.

____________________________________________________________________

Vegetable culture: a primer for amateurs, cottagers, and allotment-holders

By Alexander DeanMacmillan and Co., 1896

Shallots.

These are closely allied to Onions, especially the Potato Onion now so seldom grown, yet useful. A cluster one-third natural size is shown in Fig. 13. Small bulblets should be planted early in well prepared soil, in rows 12 inches apart, the bulbs being 8 inches asunder in the rows. From these small bulbs break out numerous others until during the summer quite large clusters are formed, and when ripe are pulled, dried, and stored. They need other

wise simple culture such as being frequently hoed to keep the soil clean. The common Shallot is the smaller, but by far the nicer for flavouring, as it is of a pleasant, delicate nature. The large or Jersey Shallot is reddish and of coarse texture. It is not so highly favoured as is the other variety. It used to be the custom of cottagers in some districts to plant Potato Onions on the shortest day, December 21st, weather permitting, and take them up on the longest, June 21st; but in very early spring planting both of these underground Onions and Shallots answer equally well.

____________________________________________________________________

Fruit recorder and cottage gardener, Volume 2

1870

Potato onions are not grown from seed, but are raised from the bulb multiplying in itself: First, you set out the small onion; this grows till it becomes a large onion the first year. You plant the same onion the next year again, and it produces two or three ordinary sized onions, and, if pure, some ten or twelve small sets around them. These small sets are again planted for large ones, the following year, but those that grow inside should not be planted for seed, for if they are the seed will soon run out.

____________________________________________________________________

Report [of the Commissioner of Agriculture]

By North Carolina. Dept. of Agriculture 1905

Sets of Yellow and White Potato onions can be used for the same purpose (editor, referring to the culture of early green bunching onions), and are planted in the same way, but the Queen is far superior for this crop. The Yellow Potato onion sets will make a fine early ripe crop If sold as soon as ripe, in late June, but they must be disposed of early, as they will not keep and are only in demand when the market is bare of ripe onions, before the Northern crop comes in.

____________________________________________________________________

Annual report of the Department of Agriculture for the ..., Volume 19, Part 2 1912

"Multiplier" or "potato" onions are compound bulbs. Instead of having a single heart or core like the ordinary onion, each bulb may have two to half a dozen cores. These bulbels should be separated and planted singly, for if left in the original "potato" they crowd each other in growing like "sets." When given room they make a very rapid growth and are soon ready for pulling to be eaten or sold. But if left in the ground through the season, each bulbel will "multiply" and make a large compound bulb like the one from which it came. Multipliers also send up fruiting stalks but are not so sure to bloom as the other kinds and growers do not desire that they should, so they usually "nip them in the bud," preferring to propagate by the multiplying bulbs.

____________________________________________________________________

Vegetable growing

By Jesse George Boyle Lea & Febiger, 1917

The potato onion produces green onions very early in the season. It propagates itself by means of its vegetative parts, by a division of the bulb. Large bulbs of this onion are planted in the spring or autumn, and about the parent bulb is produced a large number of bulblets or small bulbs. The bulblets are planted in the autumn and produce green onions early the next spring. The date of planting is from October first to fifteenth. The small potato onions are planted 3 inches apart in the row, and the rows 15 to 18 inches distant. It is generally desirable to mulch the rows after the ground is frozen to prevent alternate freezing and thawing, which may seriously injure or even kill the seed and cause it to rot. The mulch is removed in spring as soon as growth starts.

____________________________________________________________________

The Encyclopedia of Practical Horticulture:

a reference system of commercial horticulture, covering the practical and scientific phases of horticulture, with special reference to fruits and vegetables (Google eBook)

The Encyclopedia of horticulture corporation, 1914

Certain types and varieties of onions, including the "top onions" and the "multipliers" or "potato onions," are extremely hardy and may remain in the open ground throughout the winters of our Northern states, especially if given slight protection. These types are, however, not adapted to growing for market, except as green onions, "peelers," or "bunchers," to be sold during the early springtime. In certain sections of the South Atlantic coast region large areas of the top and multiplier onions are grown for this purpose.

____________________________________________________________________

The Cultivator, Volume 2

By New York State Agricultural Society, 1845

POTATO ONIONS.

From some remarks upon this species of onion, in the October number of the "Cultivator," it seems that farmers generally are not much acquainted with it. A brief description of its qualities and the mode of cultivating it, may therefore be acceptable to some of your readers.

Its mode of propagation is peculiar. A large onion, set in the ground early in spring, breaks into several (5 to 15) separate onions, which grow in a cluster of three or four good sized bulbs at the bottom, and a number of small ones lying on the top. These last vary in size from that of a nutmeg to that of a small hen's egg. The small ones arc the seed for the next year's crop. The smallest will grow into very large, single bulbs; while the larger ones will grow into two or three middling sized onions. The average annual increase, taking Large and small together, is about tenfold.

This description will readily suggest the proper mode of cultivation—which is to set out the small onions for the purpose of producing the large ones, for table use— and to set out a sufficient number of large onions for the purpose of producing the small ones for seed. The first should have a moderately rich soil, the last a soil rather barren.

The onions should be put into the ground as early in spring as the season will admit. After the ground is made mellow, set the onions in rows far enough apart to allow a hoe to pass between them. They may stand 3 lo 4 inches apart in the rows. Just cover them with earth. They may be stuck into the ground with the thumb and finger. They need no further care, but to be kept free from weeds.

To preserve them, they are gathered with a potato hook, as soon as the tops are dried, and then spread for a few days on the barn floor, or some other dry place. I formerly kept them over winter on a scaffolding in my barn; but having lost about 70 bushels by the severe winter of 1834-5,* (thermometer 23° below zero,) I have since put them into my cellar, which happens to be a very dry one, where they keep perfectly well, on a crib with a bottom of laths far enough apart (\ of an inch) lo permit a circulation of air through them. Thus managed they keep longer than any other species of onion. I have them suitable for cooking the year round.

In their eating qualities, I do not discover any difference between them and other onions. But for cheapness of cultivation, certainty of crop and amount of produce upon a given space of ground, they surpass all others.

There is a sort of Eschalot, that has been cultivated and sold for the potato onion. Wherever this fraud has been practiced it has given the onion a bad name. The genuine article, properly cultivated, has, I believe, been universally approved and highly valued.

* A curious fact in physiology came under my notice, the spring following, that deserves to be 'mentioned, though it is foreign to my subject. The rotten onions were thrown out in the spring into the barnyard, where some of them were eaten by hens. This strange food gave our eggs a most unimaginable taste—loathsome and nauseous beyond all description.

____________________________________________________________________

Making horticulture pay: experiences in gardening and fruit growing

edited by Maurice Grenville Kains, Orange Judd company, 1909 - 276 pages

"Last November," writes J. G. Orsburn of Kentucky, " I planted 125 acres in potato onions. The land was well manured with chicken and stable manure mixed. It was broken deep and close, and harrowed nicely. The rows were laid off 3^2 feet with a garden plow, and the onions were covered 4 or 5 inches deep to keep them from freezing out of the ground in winter. No more attention was paid to them until the opening of spring, when the ground was dry enough to work. Then I cultivated shallow, and kept it up every ten days, or after every rain, until the onions had matured. The cultivation was done with a garden plow and was never more than 3 inches deep, which left the onions a good, firm seed bed. I harvested them in July, and the plat yielded at the rate of 300 bushels an acre. The onions were as large and fine as any I have ever seen. The soil is designated as Miami silt loam."

____________________________________________________________________

The works of Martin Doyle. [pseud.], Volume 2

By Martin Doyle W. Curry, 1836

POTATO ONIONS

Should be planted in December or January, on well manured ground, at ten or twelve inches apart; and from twelve to sixteen inches between the rows.

In June or July they may be dug out, and when well dried, hung up to keep.

An approved mode of treating these, is, when the leaves are full grown, to draw the earth away from the bulb as far as the fibers, forming a basin round the root; it then throws out fresh bulbs, and they all ripen well.

The same method succeeds with Shallots, and prevents them from rotting.

____________________________________________________________________

Circular / Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College and ..., Issues 8-70 1915

Multiplier or Potato onions are commonly used for supplying green onions. These are grown from sets which divide continually, none of the bulbs ever attain much size. The sets are usually planted in the fall in the same manner that spring onions are planted. The following spring each set will produce from six to a dozen green onions. If a few of the onions are left they will remain until the following year and produce again.

____________________________________________________________________

Journal of horticulture, cottage gardener and home farmer, Volume 34

Journal of Horticulture Office, 1878

The Potato Onion grows in clusters, which are divided and planted annually. It may be; planted at the same time as the autumn-sown Onions are transplanted from the seed bed; indeed, we generally follow up these on the same piece of ground with the Potato Onions. The whole crop is lifted in June or July and stored like the other crop. When any are •used the clusters are divided and a few of the best left for planting again. When planted the bulbs are not wholly covered, but about the time they are fully swelled all the soil is removed from round the bulbs, so as to allow them to swell freely and ripen at the same time.

____________________________________________________________________

Dreer's Open-Air Vegetables:

A handbook based on recent field observations and talks with gardeners

H. A. Dreer, 1897 - 148 pages

Potato Onion. Potato or Multiplier onions increase by division of the bulb. A small bulb planted in spring will produce a large bulb in a comparatively few weeks. A large bulb planted in spring will, by division, produce from six to ten small bulbs. This onion is much planted in the South in autumn for scullions. It is grown in the North as a summer onion, to some extent. Large specimens of it (the yellow variety) were noted in Rhode Island in July, 1896. It is said to be free from attacks of maggot, but is liable to some other troubles. To perpetuate the stock the practice is to plant large onions and small bulbs at the same time.

____________________________________________________________________

The American Home Garden: Being Principles and Rules for the Culture of ...

By Alexander Watson (gardener.) Harper & Brothers, 1859 531 pages

POTATO ONIONS.

Potato onions are so called from their habit of producing their bulbs just below the surface of the ground. The large roots of these onions are planted, in the same manner as above directed for top onions, to furnish the sets, and these, in turn, produce onions for use. Unless raised with special care, they are apt to be strong and unpleasant. To have them good, it is necessary to divide the sets in the spring until each has but a single heart; then set them out in very rich, light soil, at the ordinary distance for onion sets, four inches apart in rows a foot wide, and cultivate them faithfully by frequent hoeings and top dressing, or the use of liquid manure (see p. 35), and they will yield you fine large onions, of a very mild and agreeable flavor.

____________________________________________________________________

Garden and farm topics

By Peter Henderson P. Henderson & Co., 1884 - 244 pages

Potato Onions.

These are increased by the bulb, as it grows, splitting into six, eight, or ten sections, which form the crop from which the "set'' or root for next season's planting is obtained. The sets are planted in early spring, in rows one foot apart, the Onions three or four inches between, and, like the Onions raised from sets, are generally sold green, as in that state they are very tender, while in the dry state they are less desirable than the ordinary Onion.

____________________________________________________________________

Market growers journal, Volume 7, 1910

Potato Onions.

I planted some small Potato Onion Sets last fall instead of large Onions, and I have all small ones. From five bushels of Sets I have about two dozen large Onions. Some have made as many as a dozen small Onions from a Bet. They made a large growth last fall. Did I plant these too early last fall or have they run out as a neighbor tells met Will they do for planting again this fallf <W. J. B., Virginia.

If your Potato Onions are the white variety you will find that they never make very large Onions, but are good for early green Onions. If they are the regular Yellow Potato Onion the growth is probably the fault of the -soil or fertilization, for small Sets should at least make a big Onion and some Sets too. Early planting has nothing to do with it. I always plant the Potato Onion in September to get a strong fall growth. I fertilize in the furrows heavily, and make a bed over the furrow.and set the Sets deeply in the bed, as a winter protection, and in early spring pull the soil away from them so that they will make their bulbs on the surface of the ground; for they should have only their roots in the ground when swelling. Deep planting may have been the cause of your trouble. With heavy fertilization and proper planting and cultivation the Sets will be all right.

____________________________________________________________________

Gleanings in bee culture, Volume 20

A. I. Root Co., 1892

WINTERING OVER POTATO ONIONS.

On pages 339 and 340, Mr. A. F. Ames, of Tennessee, speaks of wintering potato onions; and it seems a surprise to you that they, being planted a month later than other varieties, wintered well. Perhaps if friend Ames had planted the others at the same time, they might have wintered as well. I do not know anything about those; but we have grown potato onions for the last 20 years with success, and but very little loss, with the exception of two or three years when we had over two-thirds of a crop. We always calculate to plant about the 10th of October; in a warmer climate I should think better, a little later, so the onion would get well rooted before it freezes up, not putting on your mulch until the ground is well frozen, so you can wheel your manure on with a wheelbarrow. This mulch will then keep the ground from thawing and freezing, which rots the onion. That is how we had our losses. It would freeze a trifle, and then thaw. Perhaps Mr. Ames put on his mulch before the ground was frozen, and they were kept too warm, and smothered. You might get some information on this subject from T. w. (irlner, of La Salle, N. Y., who has tried to winter several kinds. I was there in March. They were coming up then; but how well he succeeded I do not know, as I haven't heard from him. H. F. Gressman.

Hamburg, N. Y., May 9.

SWAMP MUCK FOR A MULCH.

I noticed with interest what was said in May 1st Gleanings in regard to onions wintering when planted in the fall. There are a great many of the potato onions raised here for market. We aim to plant them as late in the fall as the ground can be worked, some as late as Dec. 1. The later they are planted, the better they winter. The best mulch I have found is muck from a marsh near by. It protects the onion perfectly, can be left on. and keeps the ground from getting dry and hard in the spring. Hay or fodder, or straw manure, is apt to rot them.

Ada, O., May 11. Jac. Guisingly.

____________________________________________________________________

Onions, and how to raise them

By James John Howard Gregory

Observer Office, 1865

Potato Onions, or multiplying onions, are a thick, hard fleshed variety, very mild and pleasant to the taste, and very poor keepers, unless spread very thinly in some dry apartment. They are propagated by planting the bulbs in drills, fourteen inches apart, the larger ones four to six inches apart in the row, and the smaller ones two inches. The small ones rapidly increase and make onions from two to three inches in diameter, while the larger ones divide and make from four to a dozen or even sixteen (usually from five to eight) small, irregularly shaped onions. It will be seen that the larger bulbs answer the same purpose as the seed in the common onion; hence to have onions both for sale and yet maintain the stock, it is necessary that both sizes should be planted.

The Potato onion should be indulged for its best development in a soil rather moister than the varieties from seed. The advantage of the Potato onion is its earliness, and the fact that it is not as liable to injury from the onion maggot, when that abounds, as the common sorts. I have seen an instance where on half an acre of each growing side by side, the common onion (that raised from seed) was almost wholly destroyed, while the Potato Onion was nearly uninjured.

Shallots differ from Potato Onions principally in their characteristic of always multiplying; a shallot never grows into a large round onion; but always multiplies itself, forming bulbs that average more oblong and are usually smaller than those of the Potato onion. 1 find them occasionally pushing a seed shoot, which I have never seen in the Potato Onion. Their habit of growth is finer, making a longer and more slender leaf than the Potato Onion. They are mild of flavor and greatly excel every other variety of the onion family in their keeping properties; with little care they may be kept the year round. All seedsmen do not know the difference between the Potato Onion and the Shallot. Within a few years I have twice had shallots sent me under the name '-Potato Onion."

Top Onions are propagated from little bulbs which grow in this variety where the seeds grow in the common sorts. They grow to a large size, are pleasant, mild flavored, rather coarsely and loosely made up, and have the reputation of being poor keepers. Raised like the Potato Onion.

____________________________________________________________________

Annual report of the American Institute, on the subject of agriculture, Volume 5

By American Institute in the City of New York 1847

POTATO ONIONS.

On the cjlture of onions in Russia, from the imperial Economical Society of St Petersburg!), by Mons. Sailtet.

The weekly Journal of Mussehl, reports the method of cultivating onions adopted in Russia, which consists in cutting the onion into four parts, leaving the quarters united at the root, and the onion having been first hung up and dried in smoke. For want of fresh onions, the smoke dried, still full of sap were quartered down to the roots, and being planted, each produced four fine onions, each of which had its seed stalk. It seems this mode is unknown out of Russia. The onion thus treated is not that from seed, it is the potato-onion.

Baron Foelkersahm, a member of the society, thinks it his duty to state, that he has on his estate, followed this method for thirty years, and has constantly had abundant crops.

____________________________________________________________________

Bulletin, Issues 57-88

By North Carolina State College. Agricultural Experiment Station

Agricultural Experiment Station, North Carolina State College, 1888

Potato onions should always be planted in the fall in the location in which they are to remain. These are the earliest ripe onions in the market, and can be shipped from North Carolina in June, at a time when the Northern markets are bare of ripe onions, and always bring a good price. But they are bad keepers, as all the dealers know, and there is no sale for them after the Northern onion crop comes in. Therefore they should be shipped as soon as ripe, and only the small sets kept for fall planting.

____________________________________________________________________

British farmer's magazine

James Ridgway, 1852

COTTAGE-GARDENING IN CORNWALL.— Onions.—These find a place in, I may say, every garden in this neighbourhood. They seem to be used very much by the cottagers, and many of them pride themselves a good deal on the crops which they raise, in the management of their onion-beds, in preparing the ground, for instance, and the proper time for planting them, and their after-management. In all these respects a great difference prevails here. I have seen but very few, if indeed any, seed onions growing in the gardens of the cottagers in this place. When I enquire of any of them if the onions they grow are seed onions, ' Oh, no, sir," is the reply ; " we never till any seed onions." "What, then?" "Oh, the potato onions. We are always sure of a crop with them." I shall just state some outline of what is practised by a few persons, and this may be taken as a fair index to the rest. In preparing the ground, I have not seen any of the cottagers ridge it, as is generally done by professionals ' up the country'—that is, towards London, from here. They generally bank it. These banks may be from three to five feet wide at the bottom, and all the soil for a foot or two on each side thrown upon this space, making a round-like bank. This is a very common method of winter fallow. Some use this mode of preparation previous to planting their onions. Those who plant them early in winter, of course, cannot allow their ground to derive much good by either ridging or banking of it, Now, as to the digging and planting, all seem anxious to give the ground at this time some good dressing, and dig it over " very nicely." After this is done, they plant their onions in rows, of some four or five In a bed, generally six or seven inches from row to row, and from four to six apart in the rows. Some plant them early in winter; others about the beginning or middle of February, and a few in March. A few days ago I saw a good bed of potato onions all covered over with seaweed to the depth of some four or five inches, and the onion tops six or eight inches above this covering. This Is both as a means of protection in severe weather, and of enriching and manuring the ground; and again, many of these cottagers (especially if they do not keep a pig) are very careful in saving all the soap suds, and whatever else they can in the shape of dirty water, and with this they regularly water, or rather manure, their onion beds. By this means they are often very good and large onions, and arrive at maturity earlier than seed onions sown early in spring. So they can plant broccoli after them (of these they have a variety that grows very large in this county) or flat-pole cabbages: these are almost universally grown by all classes hereabout for common use; others sow turnips—many preferring the Sweed turnip*, or Rodibakers, as they are generally termed here by the cottagers. G. Dawson.

___________________________

Journal of horticulture, cottage gardener and country gentlemen, Volume 11

G.W. Johnson, 1866

Potato Onion.—Your correspondent, "G. 8.," in the Number for the 17th inst., wishes to know if any of your readers has, like himself, found their Potato Onions refuse to increase in number. Small bulbs when planted always grow large, and rarely ever split; but good-sized bulbs always divide into from two to seven bulbs, or even more. I often wonder that Potato Onions are not more grown, as by deep culture, with plenty of manure and watering well with weak manure water during the growing season, a heavier crop may be obtained from them than from any other Onion which I hare tried. We always selected our Onions for showing from them, and were generally successful. Their only fault is their not keeping late in the Spring. We always grow James's Longkeeping, or some similar , for late use.—-W. C.

____________________________________________________________________

Gardeners chronicle & new horticulturist

Haymarket Publishing, 1897

Besides the vegetables raised and cultivated in hotbed frames, large quantities are grown in the fields. These fields are divided into beds 1.75 meters (about 5 feet 9 inches) wide, the length being indefinite; and the beds are separated by alleys 0.7 meters (27 inches) broad, which are thrown out by the plough, and the earth thus loosened is cast over the beds, so that a bed has a height of 40 to 50 cm. Cart-roads do not exist. In the middle of each bed a row of Brunswick Cabbage is planted, on each side of which a row of plants of the Russian Grape-Cucumber or Gherkin is planted, which is a sort the bine of which does not spread widely. Next to these, on each side, come Red Beets; and lastly, as an edging all round a bed, one row of Potato-Onions is planted.

This method of planting is universally followed in the Wilna district. The leaves of the Potato-Onion are constantly cut, just as we do with our Chives, and these leaves form a part of the daily food of the Russian peasantry, who live for weeks on nothing better than black (brown) bread and some finely shred Onion-leaves. In Nischni -Novogorod I obtained fresh caviare served with finely shred Onion-leaves, which, to us Western Europeans, seemed a horrible mixture. The Ogorodniki are of the opinion that by cutting the leaves of the Onion they increase the size of the bulb. However that may be, the Onions taste very nice eaten in the following manner :—First a slice of dry roll, and on the top of this a slice of Onion, above that one of Tomato strewed with caviare.

The first plants to become fit for consumption are the Potato-Onions, whose leaves, as I have remarked, are eaten by the folk with much gusto, and not despised even by the well-to-do. The Russian farmer is easily satisfied—a chunk of dry black-bread, and slices cut from a bundle, one and one half inch in diameter, of Onion-leaves, eaten as one consumes a sausage, serves for his mid-day meal. Onion-leaves are eaten in soups and with cold dishes.

In order to prevent the Potato-Onion from running to seed, they are, in the winter, exposed to a course of fumigation with wood-smoke for twenty-four hours. The cultivator continues to cut the leaves of the Potato-Onion up to the time when they begin to wither naturally. When the Onion-crop ceases to be productive, the Gherkin fruits begin to mature.

____________________________________________________________________

Intensive farming

By Lee Cleveland Corbett

Outing Publishing Company, 1913 - 146 pages

.....Market gardeners in the vicinity of every large town and city grow a quantity of early bunch onions, either from sets grown from seed as above described or from another class of onions known as Potato Onions or "Multipliers." Potato Onions are hardier than most varieties grown as sets from seeds. The Potato Onion perpetuates itself chiefly by subdivision of the large bulbs, each large bulb splitting up into a number of smaller ones, each of which is planted out to be harvested for green bunching or allowed to grow to maturity to be used next season to increase the planting stock by again splitting up into several bulbs.

....while Potato Onions are usually planted in the autumn, and in those localities where they need winter protection mulched with straw or coarse litter.

____________________________________________________________________

Gardening for young and old:

the cultivation of garden vegetables in the farm garden (Google eBook)

Orange Judd Company, 1883

THE POTATO ONION.

The cultivation of Potato Onions is similar to that of onion sets. The small potato onions are planted early in spring, in rows fifteen inches apart, and four to five inches distant in the row; keep the land clean, and that is all there is to be done. Each small bulb will make a large one. The next spring set out some of the large bulbs that have been saved for the purpose, and each will give a cluster of small ones to be planted the following year. This is the usual routine, but generally a share of those planted will split up into several small ones instead of making one large onion.

____________________________________________________________________

The American agriculturist, Volume 11

By Orange Judd Publishing Company, Inc. (New York)

pg 4

Potato Onions.—The large potato onion is beginning to attract notice among farmers as well as market gardeners. There are three kinds of potato or hill onions : one small; an old variety known by various names, as tho Bunch Onion, Hill, Cluster, and Multipliers; and a later kind known as the Egg Onion, from its resemblance in form to an egg—all of which are propagated only from bulbs or sets. The two latter sorts are worthless compared with the large "English Potato Onion," when it can be obtained; but the scarcity and high price of the seed has prevented its extensive cultivation. Being very early, and for this reason commanding as good or a better price in June and July as they would the following spring for seed, the stock is kept down to the wants of the market gardeners; hence but few find their way into the market for seed, and the demand, as far as I have known, has never been supplied. They are very easily cultivated, and a sure crop; increase about four or five-fold, that is, five or six bushels for one; and the expense of cultivation is a mere trifle, as the ground may be occupied with various summer crops, with little or no detriment to tho onions or the other crops.

My method of cultivation, which has been perfectly satisfactory for three years, is to plant them in the fall, or as early in spring as practicable, in rows about two and a half feet apart, and set them from four to eight inches apart— Rural New Yorker.

____________________________________________________________________

Successful Farming

WHEN TO PLANT POTATO ONIONS

Frequently it is difficult to secure and get onion sets planted early enough in the spring to produce fine, tender onions for table use as soon as most folks wish them. All this worry and labor can be avoided by planting onion sets in late autumn.

November is a good time for this work The earth is as a rule in excellent condition, and if it is not, it is easier to put 11 in good shape than during the wet early spnng months.

Sets of any kind will produce good young onions in early spring, but the best to plant is the variety known as the potato onion. These are quite large, but the smaller ones may be used for autumn planting, and will produce from five to ten young onions the following season. If the soil is good, and a liberal coating of wel rotted manure is used to make the Sol rich and to provide a light mulching, the onions will start to grow quite early.

The onions will, if allowed to grow, produce a clump of fine onions suitable for •winter use.

Reliable seed houses can supply either the seed or the onions from which a start can be secured of these multiplier or potato onions, and when once secured they will remain with you.—J. T. T.

____________________________________________________________________

American gardening, Volume 11 1890

Sowing.—Onions are propagated as follows: I, seeds; 2, sets; 3, top-sets or top-onions; 4, multipliers or potato-onions; 5, rareripes. The first two methods are the most common and important, though the potato onions are valuable in some sections, especially farther south.

pg 171

Potato onions, or multipliers, are the earliest and hardiest of all onions, and they are the chief sort raised by truck growers in the south for early market. Prepare the ground as for seed onions, making the rows one foot apart and set the bulbs five or six inches apart in the row, setting so deep as to just cover them. Press the soil close to them. When they have started, loosen the soil by using a scuffle hoe. When the tops wilt or fall down, pull and top, leaving one inch of top on.

____________________________________________________________________

The new onion culture: a complete guide in growing onions for profit

By Tuisco Greiner, O. Judd Company, 1903 - 114 pages

CHAPTER X

Onion Varieties

With reference to the methods of propagation, onions may be divided into three classes: (I) Onions produced by division of the bulb; (2) onions produced from top sets or button onions, and (3) onions grown from black seed. The last named may be separated into two subdivisions, namely, American and foreign types.

According to Professor Bailey's Annals of Horticulture, about twenty kinds of multipliers, potato onions and sets were offered by American dealers in 1889.

The leading variety of the first class (onions produced by division of the bulb) is the Potato onion or Multiplier, shown in Fig 47.

This is most largely grown in southern localities. The yellow variety has been in cultivation for many years, while the white sort is of much more recent introduction. The bulbs are thick, compact, tender if eaten soon after pulling, and very mild and sweet in flavor. Fall planting is generally resorted to with this variety, the sets being placed in drills four or five inches deep. As the name "Multiplier" indicates, if a large bulb is planted, division occurs during the season of growth, resulting in the formation of from three to ten or more bulbs from the parent. If sets are planted, they will make single large onions, but not multiply. The plants begin active growth very early in the spring and may be bunched and marketed at a good profit, or may be allowed to mature. In the milder sections of the South the Potato onion will grow during the entire winter. The mature bulbs should be stored in thin layers in a dry apartment to insure their keeping. This variety is rarely, if ever, affected by the onion maggot. From the fact that the small bulbs increase in size and the large ones multiply, it is necessary to plant both sizes in order to secure onions for market and also maintain the stock.

Shallots are frequently mistaken for the Potato onion. They differ from it in throwing up an occasional seed shoot and in the bulb always multiplying, which is not true with small Potato onions. The bulbs are more oblong in shape than the Potato onion. Shallots are small, may be kept the year round, and possess a mild, pleasant flavor.

ONION GROWING IN THE SOUTH

page 107

The yellow Potato onion is about the earliest ripe onion that can be put on the market, and it generally pays very well, because the market is at that time pretty bare of ripe onions. But the Potato onion must be sold as soon as ripe, for it is a poor keeper. It makes no seed, but produces offsets from the bulbs, which are set in the fall as other sets, a small set making a big onion and a larger one two to three of

marketable size. There is another onion of the same character but white in color, which is used at times for early green onions. This one never grows as large as the yellow Potato onion, but is one of the best keepers, and its white color makes it desirable for the bunching in spring.

____________________________________________________________________

The country gentleman, Volume 25:

A journal for the farm, the garden, and the fireside, devoted to improvement in agriculture, horticulture, and rural taste; to elevation in mental, moral, and social character, and the spread of useful knowledge and current news.

L. Tucker, 1865

POTATO-ONIONS.

crop,) required for seed, and the extra labor of setting! out and cultivation, forbid the cultivation of this j onion as a field crop, unless their superior excellence J would command for them a much higher price than I is obtained for the common onion.

"N. E. C." asks for information about these onions. I have grown them for fifteen years. A good garden soil in high condition, is essential to success. Fall plow if you can—work in the spring early. Keep a smooth level surface. Mark in rows 15 inches apart. I In this mark I run a wheel hand plow to deepen it; in this set your onions; if large, 4 to 6 inches apart, and less for the small, say 2 to 4 inches, just covering with earth, and placed so as to be nearly even with the surface. The seed grows in the centre of the large onions—nq,stalk, and the onions producing seed or sets are good as any. I have always used them mainly for green onions for market, and consequently could not tell the yield, but presume 300 to 400 bushels might be grown to tire acre. I clear off what is left in July, and plant celery. A. S. Moss.

Fredbnia, N. Y.

Eds. Co. Gent.—I notice an inquiry for potato onion seed. The potato onion does not produce seed, but re-produces itself somewhat like the potato— hence the name. You set out a perfect onion in the spring, and as thb top grows the bulb rots and sloughs off, leaving from five to ten small germs, from which the tops spring. These make small onions, the whole weighing but little if any more than the original onion. While in this stage of growth they make a very fine salad onion. Any number of these germs may be plucked from the roots for that purpose, and what remains will be all the better for it. These small onions are set out the second year, just as you would set out top onions, and produce the perfect onion. They grow to a fine size, and are very mild, crisp and tender, having very little of that pungent, tear-producing flavor of the common onion. They are So very mild, that persons fond of that root will eat them, with the addition of a little salt, just as they would a raw turnip or an apple. B. C. Hood.

____________________________________________________________________

How the Farm Pays:

The experiences of forty years of successful farming and gardening by the authors

P. Henderson, 1884

POTATO ONIONS

are increased by the bulb as it grows, splitting into six, eight or ten sections, which form the crop from which the "set" or root for next season's planting is obtained. These are planted in early spring, in rows one foot apart, the onions three or four inches between, and like the onions raised from sets, are generally sold green, as in that state they are very tender, while in the dry state they are less desirable than the ordinary onion.

____________________________________________________________________

Farmers' bulletin, Issues 26-50

By United States. Dept. of Agriculture:

1900

Potato Onion (Yellow and White Multiplier).—The potato onion is most largely grown in Southern localities. The yellow variety has been in cultivation for many years, while the white sort is of much more recent introduction. The bulbs are thick, compact, tender if eaten soon after pulling, and very mild and sweet in flavor. Fall planting is generally resorted to with this variety, the sets being placed in drills 4 or 5 inches deep. As The name "Multiplier" indicates, if a large bulb is planted, division occurs during the season of growth, resulting in the formation of from 3 to 10 or more bulbs from the parent. If sets are planted, they will make single large onions, but not multiply. The plants begin active growth very early in the spring, and may be bunched and marketed at a good profit, or may be allowed to mature. In the milder sections of the South the potato onion will grow during the entire winter. The mature bulbs should be stored in thin layers in a dry apartment to insure their keeping. This variety is rarely, if ever, affected by the onion maggot. From the fact that the small bulbs increase in size and the large ones multiply, it is necessary to plant both sizes in order to secure onions for market and also maintain the stock.

____________________________________________________________________

Cyclopedia of American Horticulture:

Wilhelm Miller, Macmillan, 1901

Multipliers are shown in Fig. 1532-3. Instead of containing a single "heart "or core, as in most Onions, it contains two or more. When the Onion is planted, each of these cores or bulbels sends out leaves and grows rapidly for a time; that is, the old or compound bulb separates into its component parts. The growing bulbels may be pulled and eaten at any time. If allowed to remain in the ground, each of these bulbels will make a compound bulb like that from which it came. Sometimes flower-stalks are produced from multiplier or potato Onions. The best results with multipliers are secured when the bulbels are separated on being planted, for each one has room in which to grow. Two or three kinds of multiplier Onions are known, the variation being chiefly in the color of the bulb.

RELATED POSTS: Where to Buy Potato Onion Starts, Mr Winterton's Remarkable Potato Onions, POTATO ONIONS!

Here are my tasting notes from mid to late season. The Late season extends quite late here with Lady Williams coming in at the end of February. For notes on earlier apples and my thoughts on tasting and evaluation in general, see the previous post, Red Astrachan to King David. I did not review every apple I tasted this season. If something was really good, I'm inclined to mention it, but I feel I need more time to live with many of them before I make any judgement at all. Young trees don't always produce exemplary fruit, and it can be difficult to judge when to pick and eat apples. I also reserve the right to change my mind in the future as I encounter more specimens of various apples and maybe find new benchmarks for comparison. And, as always, what does well here in sunny (often hot) Northern California might not do so well where you live, and vice versa. This time around I’ve stuck mostly to apples that I did actually really like, or had a lot of, and passed by many that were just not that interesting. Some of these fruits are presented in the order of ripening, and some aren't... if that makes any sense... if that doesn't make sense, I guess I'll just give up and get on with it.

Here are my tasting notes from mid to late season. The Late season extends quite late here with Lady Williams coming in at the end of February. For notes on earlier apples and my thoughts on tasting and evaluation in general, see the previous post, Red Astrachan to King David. I did not review every apple I tasted this season. If something was really good, I'm inclined to mention it, but I feel I need more time to live with many of them before I make any judgement at all. Young trees don't always produce exemplary fruit, and it can be difficult to judge when to pick and eat apples. I also reserve the right to change my mind in the future as I encounter more specimens of various apples and maybe find new benchmarks for comparison. And, as always, what does well here in sunny (often hot) Northern California might not do so well where you live, and vice versa. This time around I’ve stuck mostly to apples that I did actually really like, or had a lot of, and passed by many that were just not that interesting. Some of these fruits are presented in the order of ripening, and some aren't... if that makes any sense... if that doesn't make sense, I guess I'll just give up and get on with it.